17.09.2019

After crystallizing a partnership to retrieve samples from the surface of Mars and return them to Earth, NASA and European Space Agency officials are seeking government funding commitments before the end of this year to carry out a multibillion-dollar robotic mission that could depart Earth with a pair of rocket launches as soon as 2026.

The Mars sample return mission, if approved, would pick up rock and soil samples collected by NASA’s Mars 2020 rover set for launch next year. The specimens would come back to Earth for detailed analysis in terrestrial laboratories, yielding results that scientists say will paint a far clearer picture of the Martian environment — today and in ancient times — than possible with one-way robotic missions.

A preliminary signal of support came earlier this year came in the White House’s fiscal year 2020 budget request, which proposed $109 million for NASA to work on future Mars missions, including a sample return. That’s after NASA received $50 million to study the sample return effort in 2019.

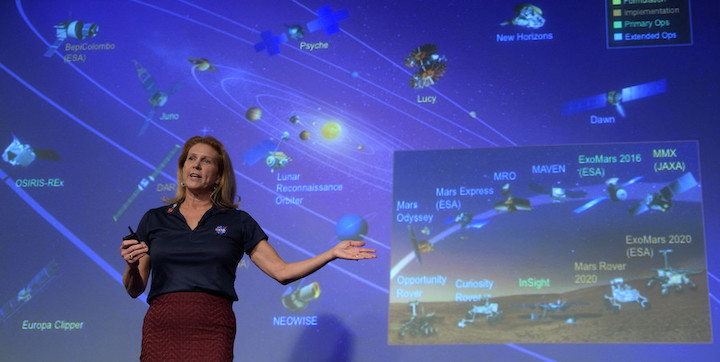

“The 2020 budget, the president’s recommended budget, included Mars sample return as a recommendation that we begin working on,” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, in a presentation Sept. 10 to the National Academies’ Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Sciences. “We don’t know the status of that through congressional funding yet because we don’t have an appropriations bill yet, but we’re hopeful that there will be some appropriations there so we can move out on this activity.”

NASA unveiled a strategy to pursue a “lean” lower-cost Mars sample return mission in 2017, a plan Glaze said would allow scientists to get their hands on fresh samples from the Martian surface as soon as possible.

But even a lean Mars sample return mission will cost billions of dollars.

When asked at the Sept. 10 meeting, Glaze said NASA’s cost estimate for a Mars sample return mission is “still pretty rough at this point” and she said she was reticent to give a specific number.

“Keep in mind, we’re looking at a collaborative approach, which helps,” she said. “It’s in the kind of $2.5 to $3 billion (range). And that number is for the U.S. side, the launch of the lander, (it) does not include the fetch rover, that’s ESA-provided. On the Earth Return Orbiter, it’s ESA-provided, but it carries a U.S. payload capture system and re-entry system.”

Senior NASA leaders in July approved preliminary plans for the Mars sample return mission put together over the last two years, including roles for the U.S. space agency, ESA, and individual NASA centers, Glaze said.

NASA and ESA signed a “statement of intent” in April 2018 to jointly work on a Mars sample return program.

“Just a couple of months ago, at NASA, we conducted what’s called an acquisition strategy meeting, which is at the highest levels within NASA, where we discuss and get approval for the various partnerships, not only with the international partners, but also the division of labor and work within NASA,” Glaze said.

Officials said multiple NASA centers will have a role in the sample return effort, including the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Marshall Space Flight Center, the Ames Research Center, and the Langley Research Center. The U.S. contribution to the mission will likely launch from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, and the Johnson Space Center in Houston is home to NASA’s sample curation lab.

“There would also be opportunities for commercial participation in various aspects, as well as additional international participation,” Glaze said.

“Hopefully, by the end of the calendar year, we’ll know what the congressional appropriation is for NASA, and whether or not that includes funding for Mars sample return,” Glaze said. “And also, in November, ESA has their ministerial meeting coming up, where they hopefully get the permission to move out and move forward with Mars sample return on their side.”

The meeting of European government ministers, set for Nov. 27-28 in Seville, Spain, will approve funding for ESA programs over the next few years. Among other space research projects, ESA will propose to government ministers a budget to kick-start development of the European elements of a Mars sample return mission.

Mars sample return missions have been studied for decades, but the concepts have never moved into full-scale development.

“Finding an affordable solution is going to be key if we are going to be able to ultimately move this forward, and not just make it another study,” said Jim Watzin, director of NASA’s Mars exploration program at NASA Headquarters.

Beyond any funding provided by Congress in NASA’s 2020 budget, agency officials hope for a more firm commitment for Mars sample return from the Trump administration in the White House’s fiscal year 2021 budget request, potentially including authority to officially kick off full-scale development.

“The president will submit his budget request for fiscal year ’21, typically in the February timeframe, and that’s when we would hear whether or not the administration has made the decision to support sample return, and in what timeframe from a budgetary perspective,” Watzin said.

NASA officials describe the sample return effort as a “campaign” sustained over more than a decade with at least three separate launches from Earth, beginning next July with the liftoff of the Mars 2020 rover from Cape Canaveral on top of a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

The Mars 2020 rover will land on the Red Planet in February 2021 at Jezero Crater, the location of an ancient dried-up river delta where water and sediments flowed into a basin billions of years ago.

The sophisticated rover carries its own miniature laboratory, with instruments to study Martian geology and search for organic molecules at finer scales than achievable by any prior mission. It also carries a weather station, a ground-penetrating radar and a technology demonstration payload to convert carbon dioxide in the Martian atmosphere into oxygen, a pathfinder for human explorers to live off the land.

But a primary goal of the Mars 2020 rover will be to collect up to 43 hermetically-sealed tubes of core samples drilled from Martian rocks. Some of the tubes, each about the size of a pencil, will be retrieved by a fetch rover launched in the next phase of the Mars sample return campaign.

“The studies have prepared both agencies to make a very informed decision around the end of 2019, and from my perspective, this is huge progress,” Watzin said. “I think we’ve got a really strong team in place, and everybody is really hopeful that we’ll get the support on both the east side and the west side of the Atlantic to proceed.”

Assuming formal approvals in the coming months, NASA and ESA officials say the sample retrieval mission could depart Earth with a pair of launches in 2026. Mars launch opportunities come every 26 months, but not all interplanetary windows are favorable for the departure of a round-trip mission, Watzin said.

“When you look at the round-trip aspects of going to and from Mars, propulsion demands are enormous,” Watzin said in July. “The physics for launching and leaving a planet, both here on Earth and on Mars, cannot support an every 26-month opportunity like we’ve been used to. There are a couple of opportunities where the energetics are manageable with a reasonable budget and reasonable technology, and the rest of the opportunities require the invention of new things. And a limited cost and affordable approach means that the invention of new things had to be restricted on any approach that we took.

“So we have two opportunities that we’ve seriously looked at, and they span from ’26 to ’29 in various shapes and forms,” Watzin said.

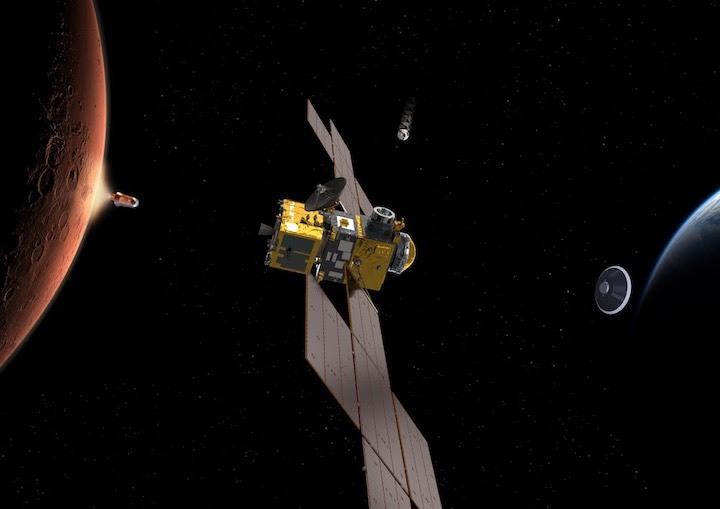

The European Space Agency will provide a fetch rover, which will arrive on Mars aboard a U.S.-built lander and then drive off the stationary platform to pick up samples collected by the NASA Mars 2020 rover. After gathering the sample tubes, the fetch rover will return the specimens to the NASA lander and transfer the materials into a mechanism to be loaded aboard a U.S.-built Mars Ascent Vehicle.

The fetch rover and Mars Ascent Vehicle will arrive on Mars aboard the same lander.

The rocket will loft the payload into orbit around Mars to rendezvous with a European-made Earth Return Orbiter, the spacecraft that will return the samples to Earth.

The U.S. lander and European fetch rover, including the NASA-provided Mars Ascent Vehicle, would launch on a U.S. rocket in 2026. A few months later, the Earth Return Orbiter and a U.S. re-entry vehicle would lift off on a European launcher.

If the sample return missions launch in 2026, the Mars 2020 rover itself could still be operating when they arrive at the Red Planet. That could give scientists a backup option to transfer the samples into the Mars Ascent Vehicle, in case the fetch rover encounters problems.

“Having an early opportunity for sample return allows us to use Mars 2020 as a player in this,” Watzin said. “We have the operational option of holding tubes on Mars 2020 as a contingency against any snafu with the fetch rover, and we have the fetch rover picking up tubes that have been dropped as a contingency against Mars 2020.”

In July, ESA released an invitation for European industry to submit proposals to build the Earth Return Orbiter. Airbus Defense and Space received a study contract from ESA last year to begin designing systems for a fetch rover, building on Airbus’s experience in building the European ExoMars rover set for launch next year, named Rosalind Franklin.

NASA engineers continue evaluating solid-fueled and hybrid propulsion options, including two-stage and single-stage variants, for the Mars Ascent Vehicle.

NASA will also supply the re-entry capsule to deliver the samples back to Earth’s surface. After release from the European return craft, the capsule will target landing in the Utah desert in 2031.

Engineers plan to return the samples without a parachute. Instead, the armored entry vehicle will crash into the ground at high speed.

Watzin said drop tests show the samples will still be in good condition after a high-speed landing, and the tubes flying on the Mars 2020 rover were designed with the no-chute return in mind.

“We believe that we can land the sample and still have them in good condition for the analysis everyone wants to do, without a chute,” Watzin said.

NASA is concerned about the risk extraterrestrial samples might pose to humans and Earth’s environment, so the entry capsule would have to be designed to withstand a parachute failure.

“We don’t want to inadvertently release the material we’re bringing home,” Watzin said. “We would have to survive the failure modes of whatever system we design, and a chute failure is … a reasonable probability failure mode. So we have to design it to work without a chute in the beginning.”

Designing the mission without a return parachute will also save weight on the spacecraft.

“The lowest mass entry vehicle is going to be with only those systems you absolutely have to have,” Watzin said. “For those reasons, we went without (a parachute in our design). We know we have to prove it.”

Asked at a July meeting of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group about using commercial vehicles, such as SpaceX’s planned Starship, for the Mars sample return campaign, Watzin said NASA is focused on using proven technology.

“We knew that we would like do this sooner rather than later, so it didn’t seem sensible to go down a path where we had to develop, from the beginning, a brand new delivery system, when the delivery systems we’re familiar with and have been successful with are adequate to support the execution of the mission,” Watzin said. “If that (Starship) capability matures and shows up, I’m sure programmatically we will take full advantage of it, but it didn’t seem to make sense, since we don’t really know what it’s going to be, or when it’s going to be there, to make it the basis for the campaign.”

If approved for a launch target in 2026, the Mars sample return mission would be NASA’s next flagship-class science mission after the Mars 2020 rover and the Europa Clipper probe, set for launch in 2020 and 2023, respectively.

Quelle: SN