17.10.2019

They could be more regular, and more destructive, than previously thought.

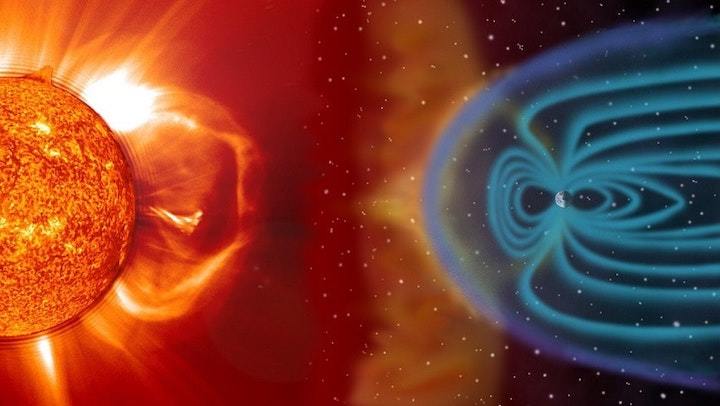

Solar blow-ups like the Carrington Event, a 1859 solar storm long believed to be the largest in the history of modern astronomical observations, may be more common than previously believed, scientists say.

The 1859 event is named for British astronomer Richard Carrington, who happened to be mapping sunspots at the moment a giant flare sent a torrent of high-energy radiation streaking toward Earth.

NASA's Solar Dynamic Observatory captures a giant sunspot that spanned a little under 130,000 kilometres.

When it arrived, that radiation produced aurora (northern and southern lights) bright enough that people could read newspapers in their light.

It also created electrical disturbances strong enough to cause sparks to leap off telegraph equipment, melting wires and starting fires – an electrical surge that would be catastrophic if it were to occur today.

Dangerous as such an event would be in today’s wired world, however, solar storms such as Carrington’s were thought to be rare, worst-case examples of what the Sun could hurl at us.

But that may not be the case, says Hisashi Hayakawa, a historian turned astrophysicist at Osaka University, Osaka, Japan, and Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Chilton, UK.

In a paper published in the journal Space Weather, Hayakawa’s team sought out sunspot drawings by astronomers other than Carrington and tracked down previously unknown magnetic-field measurements and northern and southern lights descriptions from Russia, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, and Brazil.

The additional drawings gave them a more complete picture of the evolution of sunspots in the weeks before and after the event, while the other information gave them a better handle on the storm’s worldwide effects than had previously been available.

They then compared their findings to data from giant solar storms in 1872, 1909, 1921, and 1989. Based on this, they concluded that two of these – the ones in 1872 and 1921 – were actually Carrington-sized events, meaning that instead of being rare, such solar storms appear to come along once every few decades.

Daniel Baker, a space physicist at the University of Colorado's Laboratory of Atmospheric and Space Physics, applauds the new study.

“Frankly, I have long believed that there are many more ‘extreme’ events than have been appreciated in the science community,” he says.

In fact, he says, we probably had a near-miss with another one in July 2012, when the Sun emitted a blast that was likely more powerful than the Carrington event’s, but which, fortunately, bypassed us.

When the next such storm strikes, however, technological changes are apt to make it far more dangerous than those in 1859, 1872, or 1921.

Even the 1989 storm, which Hayakawa’s team found was not as strong as those three, was powerful enough to cause a serious blackout throughout the province of Quebec, Canada.

And that was 30 years ago. Today, in addition to still being vulnerable to large-scale power grid failures from such events, Hayakawa says, “we are now fully dependent on emails, GPS systems, and satellite infrastructures”.

One thing that’s needed, he says, is to invest more strongly in learning how to protect ourselves from such storms when they occur.

“Such events will happen,” he says, noting that the Japanese have learned this from experience with other catastrophes, such as 2011’s “once-a-millennium” tsunami, and this year’s “once-a-century” typhoon.

“We need to get ourselves prepared,” he says.