9.08.2019

Earth is pretty nice. but it won't stay that way

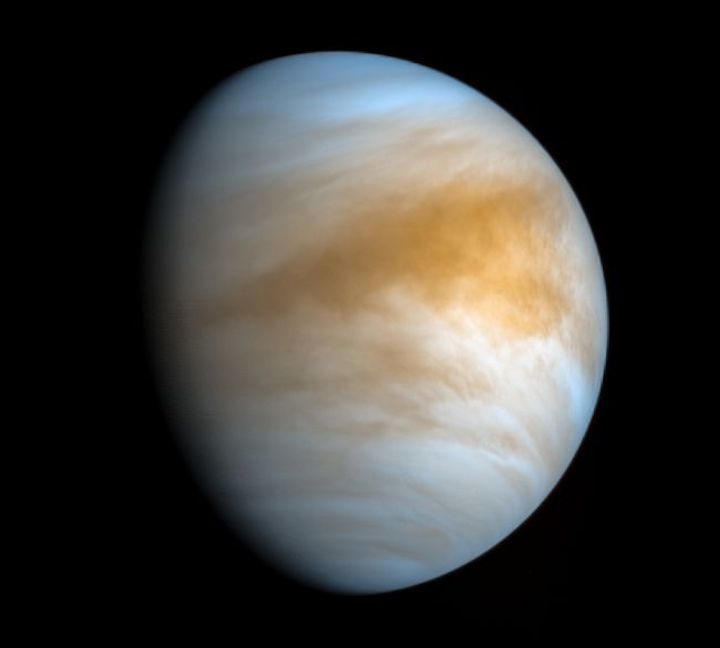

The bizarre and hellish atmosphere of Venus wafts around the planet's surface in this false-color image from the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency's Akatsuki spacecraft. Citizen scientist Kevin Gill processed the image using infrared and ultraviolet views captured by Akatsuki on Nov. 20, 2016.

Everyone wants to get off the planet Earth and go explore the solar system, without realizing just how good we've got it down here. We've got a lot of air, more liquid water than we know what to do with, a nice strong planetary magnetic field that protects us cosmic radiation, and nice strong gravity that keeps our muscles strong and our bones thick.

All things considered, Earth is pretty nice.

But still, we look to our planetary neighbors for places to visit and maybe even live. And Mars has all the attention nowadays: it's so hot right now, with everyone practically climbing over each other's rockets to get there in to build a nice little red home.

But what about Venus? It's about the same size as the Earth and the same mass. It's actually a little bit closer than Mars. It's definitely warmer than Mars. So why don't we try going for our sister planet instead of the red one?

Oh, that's right: Venus is basically hell.

Dante's journey

It's hard to not exaggerate just how bad Venus is. Seriously, imagine in your head what the worst possible planet might be, and Venus is worse than that.

Let's start with the atmosphere. If you think that the smog in LA is bad, you should take a whiff of Venus. It's almost entirely carbon dioxide and chokingly thick with an atmospheric pressure at the surface 90 times that of Earth. That's the equivalent pressure of a mile beneath our ocean waves. It's so thick that you almost have to swim through it just to move around. Only 4% of that atmosphere is nitrogen, but that's more nitrogen total than there is in the Earth's atmosphere.

And sitting on top of this are clouds made of sulfuric acid. Yikes.

Sulfuric acid clouds are highly reflective, giving Venus its characteristic brilliant shine. The clouds are so reflective, and the rest of the atmosphere so thick, that less than 3% of the sun's light that reaches Venus actually makes it down to the surface. That means that you will only vaguely be aware of the difference between day and night.

But despite that lack of sunlight, the temperature on Venus is literally hot enough to melt lead, at over 700 degrees Fahrenheit (370 degrees Celsius) on average. In some places, in the deepest valleys, the temperature reaches over 750 degrees Fahrenheit (400 degrees Celsius), which is enough for the ground itself to glow a dull red.

And speaking of day and night — Venus has one of the most peculiar rotations in the solar system. For one, it rotates backward, with the sun rising in the west and setting in the east. Second, it's incredibly slow, with one year lasting only two days.

Additionally, Venus once had plate tectonics that shut off long ago, and its crust is locked.

Yeah, Venus is hell.

So how did Earth's sister end up so twisted?

Because Venus is made of pretty much the same stuff as our Earth, and has roughly the same size and mass, scientists are pretty sure that, back in the early days of the solar system, Venus was kind of nice. It probably supported liquid water oceans on the surface and white fluffy clouds dotting a blue sky. Actually, quite lovely.

But four and a half billion years ago, our sun was different. It was smaller and dimmer. As stars like our sun age, they steadily grow brighter. So back then Venus was firmly planted in the habitable zone, the region of the solar system that can support liquid water on the surface of a planet without it being too hot or too cold.

But as the sun aged, that habitable zone steadily moved outward. And as Venus approached the inner edge of that zone, things started to go haywire.

As the temperatures rose on Venus, the oceans began to evaporate, dumping a lot of water vapor into the atmosphere. This water vapor was very good at trapping heat, which further increased the surface temperatures, which caused the oceans to evaporate even more, which caused even more water vapor to get in the atmosphere, which trapped even more heat, and so on and so on as things spiraled out of control.

Eventually, Venus became a runaway greenhouse with all the water dumped into the atmosphere trapping as much heat as possible, with the surface temperatures continuing to skyrocket.

The liquid water that had been on the surface helped keep the tectonic plates nice and flexible, in a sense adding lubrication to the process of plate tectonics. But without the oceans, plate activity ground to a halt, locking the surface of Venus in place. Plate tectonics play a crucial role in regulating the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Essentially, carbon binds to elements in dirt and rocks, and those dirt and rocks eventually get buried far beneath the surface over the course of millions of years as the plates rub up against each other and sink below each other.

But without this process, carbon that was locked in the dirt just slowly outgassed or dumped out in massive volcanic events. So, once the oceans evaporated, the carbon problem on Venus became even worse with nothing to sequester it. Over time, the water vapor in the atmosphere got hit by enough sunlight to break it apart, sending the hydrogen into space, with all that mass being replaced by carbon dioxide rising up out of the surface.

The once and future Earth

And as that atmosphere grew thicker, the conditions on the surface grew even more hellish.

The atmosphere might even have had enough drag to literally slow down the rotation of Venus itself, giving it its present-day sluggish rates.

Once this process was complete, which probably took 100 million years or so, the potential for any life on Venus was snuffed out.

And here's the worst part about the story of Earth's twisted sister. This is our fate, too. Our sun isn't done aging, and as it grows older, it grows brighter, with the habitable zone steadily and inexorably moving outward. At some point within the next few hundred million years, the Earth itself will approach the inner edge of the habitable zone. Our oceans will evaporate. Temperatures will spiral upward. Plate tectonics will shut off. Carbon dioxide will dump into the atmosphere.

And by that time, our solar system will be home to not just one hell but two.

Quelle: SC