3.01.2020

There's less water out there than we thought. But, why?

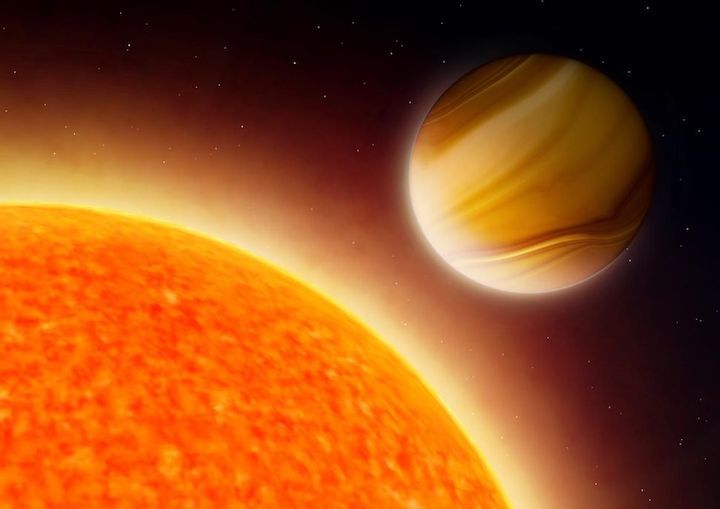

A most extensive survey yet of the atmospheric makeup of exoplanets challenges planet formation theories and the search for water on other worlds.

Water appears both common and unexpectedly scarce in exoplanets — many distant worlds have it, but less of it than predicted, a new study finds.

These findings may shed light on how planets form, including those in our own solar system, researchers said.

Scientists examined data from the atmospheres on 19 exoplanets collected by space-based and ground-based telescopes. These worlds ranged widely in temperature, from nearly 70 degrees F (20 degrees C) to more than 3,630 degrees F (2,000 degrees C), and in size, "from mini-Neptunes roughly 10 times Earth's mass to super-Jupiters more than 600 times Earth's mass," study co-author Nikku Madhusudhan, an astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge in England, told Space.com.

The scientists found that water vapor was common in the alien worlds they examined, detected in 14 of the 19 worlds.

"The fact that we are making detailed measurements of water vapor in exoplanets is remarkable, because we have not yet made any significant detection of water for the giant planets in our own solar system," Madhusudhan said. "We can measure water better with exoplanets than in our own solar system."

Besides water, the chemicals most often detected in giant exoplanet atmospheres were sodium and potassium. The amounts of sodium and potassium seen in the exoplanets were consistent with expectations given what scientists know about the planets in our solar system. However, water vapor levels were significantly lower than predicted.

"That was a big surprise," Madhusudhan said.

The predictions the researchers had for how much water these exoplanets should have possessed is based off how much water may lurk in the gas giants in our own solar system, which remains uncertain. Multiple efforts to detect water in Jupiter's atmosphere, including NASA's current Juno mission, have faced numerous challenges.

"Since Jupiter is so cold, any water vapor condenses out of its atmosphere, and we can't see it," study lead author Luis Welbanks, an astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge in England, told Space.com.

The expectations about how much water solar system gas giants should have are based on how the amount of carbon relative to hydrogen in the atmospheres of giant planets is significantly higher than that of the sun. Previous research suggested this "super-solar" abundance originated when the solar system was forming and large amounts of carbon-loaded ices and dust fell or accreted onto giant planets.

Prior work also suggested that abundances of certain elements besides carbon should be similarly high in the atmospheres of giant planets, especially oxygen, which is the most abundant element in the cosmos after hydrogen and helium. As such, this suggested that water, the most common oxygen-bearing molecule in the universe, should also be overabundant in the atmospheres of giant planets, having accreted in the form of ice as those worlds formed.

These findings suggest that when giant planets form, less ice may fall into them than previously thought. For example, if giant planets form by accreting material from the protoplanetary disks surrounding newborn stars, these worlds may accrete very different levels of chemicals such as water depending on where they form and how they move within protoplanetary disks.

"There may be ways of making a giant planet that is underabundant in oxygen and therefore water," Madhusudhan said. "By looking at exoplanets, we are reconsidering how planets may have also formed in our own solar system."

There is life virtually wherever there is water on Earth, so discovering that there is less water in other planetary systems than expected might suggest the chances of life as we know it elsewhere in the universe are lower as well. Still, "if you look at Earth, it doesn't have that much water by mass — in fact, Earth is slightly underabundant in water," Madhusudhan said. "So our findings regarding a lower inventory of water in exoplanets is not necessarily bad news for their potential for habitability."

The researchers aim to look at more exoplanets to see if they follow the pattern they detected or look for outliers that might buck this trend. "Ultimately, we are bound to find outliers," Madhusudhan said. "Nature is extremely diverse when it comes to the properties of planetary systems."

Quelle: SC