19.02.2026

Team finds previously unknown dusty, star-forming galaxies almost 13 billion years old, helping to revise the history of the universe

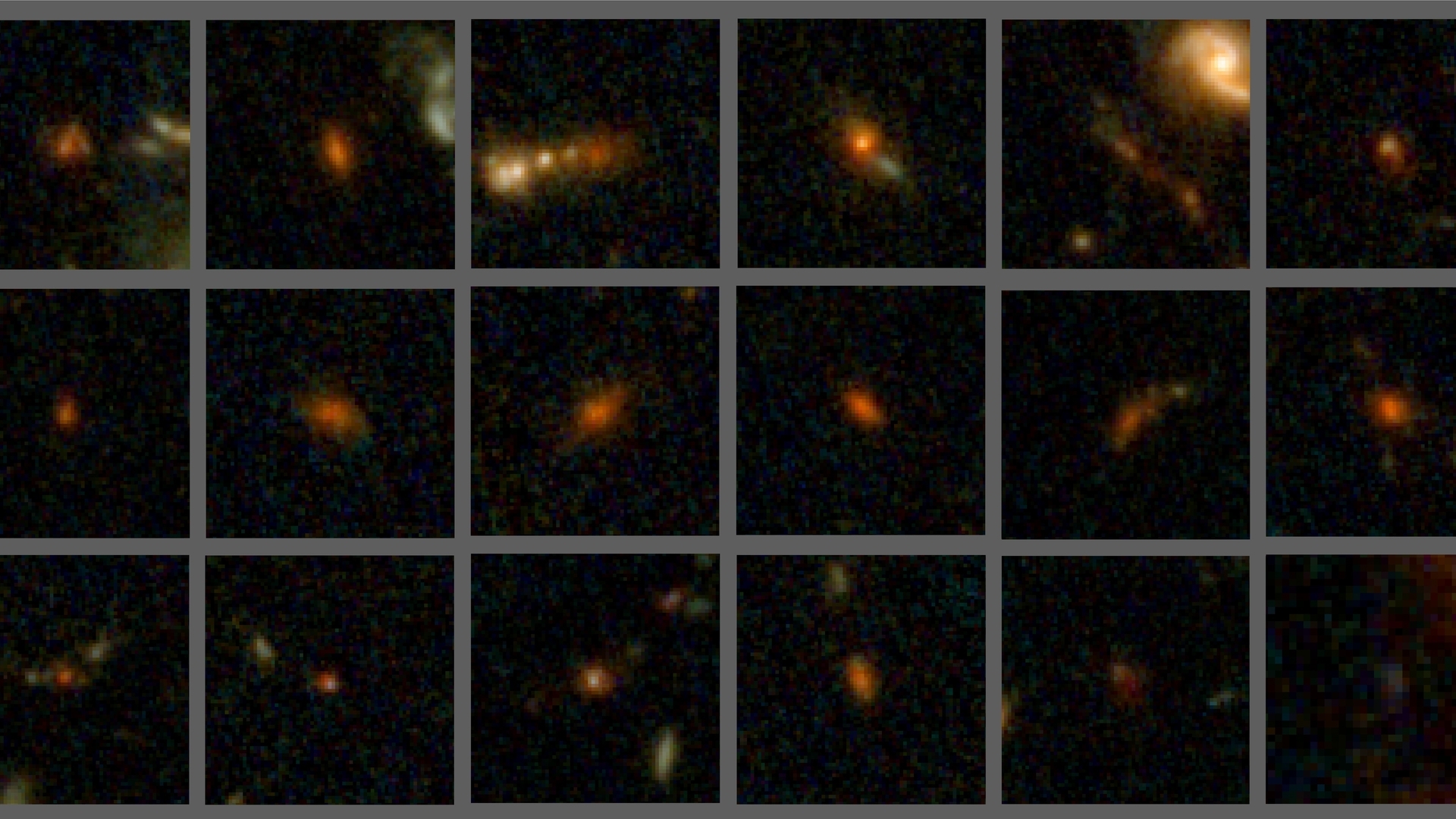

A team of 48 astronomers from 14 countries, led by the University of Massachusetts Amherst, has discovered a population of dusty, star-forming galaxies at the far edges of the universe that formed only a billion years after the Big Bang, believed to have occurred 13.7 billion years ago.

The galaxies may represent a snapshot in the galactic lifecycle, linking recently discovered ultradistant bright galaxies formed 13.3 billion years ago with early “quiescent,” or dead, galaxies that stopped forming stars about 2 billion years after the Big Bang. The new discovery challenges current models of the universe, making the findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, is a step toward revising cosmic history.

“My research involves trying to identify and understand a population of rare, dusty star-forming galaxies that were only discovered at the end of the 1990s,” says Jorge Zavala, assistant professor of astronomy at UMass Amherst and the paper’s lead author.

Part of what has made these galaxies so difficult to study is the dust, which absorbs UV and visible light, essentially making them invisible to telescopes that rely on the UV and visible parts of the spectrum.

But with the invention of submillimeter telescopes, which can see longer-wavelength light, suddenly astronomers were able to shine a light into dusty parts of the universe that had previously remained dark. As the dust absorbs UV and visible light, it also creates heat—radiating infrared energy visible to these telescopes.

Zavala and his co-authors relied on the Atacama Large Millimeter/sub millimeter Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile to first identify a population of about 400 bright, dusty galaxies. They then used near-infrared observations made by NASA’s recently launched James Webb Space Telescope to pinpoint approximately 70 faint dusty galaxy candidates on the edge of our universe, most of which had never been seen before. By going back to the ALMA data and “stacking” the observations, the team was able to confirm that these are in fact dusty galaxies formed almost 13 billion years ago.

While technical knowledge necessary to make this discovery is itself newsworthy, the real story is about what this discovery means for our understanding of the history of the universe.

“Dusty galaxies are massive galaxies with large amounts of metals and cosmic dust,” Zavala says. “And these galaxies are very old, which means stars were being formed in the early universe, earlier than our current models predict.”

Furthermore, it seems that the galaxies Zavala and his team found are related to two other sets of rare, anomalous galaxies: the ultrabright, star-forming galaxies that formed soon after the Big Bang (recently discovered by JWST), and much older, massive “quiescent” galaxies, that have essentially died and are no longer forming stars.

“It’s as if we now have snapshots of the lifecycle of these rare galaxies,” Zavala notes. “The ultrabright ones are young galaxies, the quiescent ones are in their old age, and the ones we found are young adults.”

Though it will take much more research to confirm these suggestions, if Zavala and his team’s hypothesis holds true, it means both that our current astronomical models of the universe’s formation are missing something, and that star formation occurred earlier in the universe’s evolution than previously thought.

Zavala points out that this research would not have been possible without the collaboration of scientists and institutions from across the world, including funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Quelle: University of Massachusetts Amherst

+++

Scientists observe distant jellyfish galaxy for first time

New astronomical find is 8.5 billion years old and reshapes our understanding of early cosmic evolution

Astrophysicists from the University of Waterloo have observed a new jellyfish galaxy, the most distant one of its kind ever captured.

Jellyfish galaxies are named for the long, tentacle-like streams that trail behind them. They move quickly through their hot, dense galaxy cluster, and the gas within the cluster acts like a strong wind pushing the jellyfish galaxy's own gas out the back, forming trails. The technical term for this process is ram-pressure stripping. The Waterloo scientists found this galaxy in deep space data captured by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). It is at z = 1.156, meaning we’re seeing it as it was 8.5 billion years ago, when the universe was much younger.

The data provides a rare insight into how galaxies were transformed in the early universe and challenges conceptions of what the universe would have been like 8.5 billion years ago.

The team made the discovery while examining the COSMOS field — Cosmic Evolution Survey Deep field — a particular patch of the sky that many telescopes have observed to study distant galaxies. Astronomers chose this patch because it is far from the plane of our own galaxy, and so there is little contamination from stars and dust in the Milky Way. It lies in a region of the sky visible from both the northern and southern hemispheres and free of bright foreground objects, giving astronomers an unobstructed view of the distant universe.

“We were looking through a large amount of data from this well-studied region in the sky with the hopes of spotting jellyfish galaxies that haven’t been studied before,” said Dr. Ian Roberts, Banting Postdoctoral Fellow at the Waterloo Centre for Astrophysics in the Faculty of Science. “Early on in our search of the JWST data, we spotted a distant, undocumented jellyfish galaxy that sparked immediate interest.”

This jellyfish galaxy had a normal-looking galaxy disk and bright blue knots in its trails, which are very young stars. The age of the stars suggests that they were formed outside of the main galaxy in the trails of stripped gas, which is expected in a galaxy of this nature.

Information gathered from studying this galaxy has challenged some previously held beliefs about what was happening in deep space at that time. Scientists believed that galaxy clusters were still forming and that ram-pressure stripping was uncommon. Roberts and the team made three additional discoveries that could change how we understand the universe.

“The first is that cluster environments were already harsh enough to strip galaxies, and the second is that galaxy clusters may strongly alter galaxy properties earlier than expected,” Roberts said. “Another is that all the challenges listed might have played a part in building the large population of dead galaxies we see in galaxy clusters today. This data provides us with rare insight into how galaxies were transformed in the early universe.”

To learn more about this jellyfish galaxy, Roberts and the team have requested additional time on the JWST to delve deeper into its mysteries.

Quelle: University Waterloo