9.01.2026

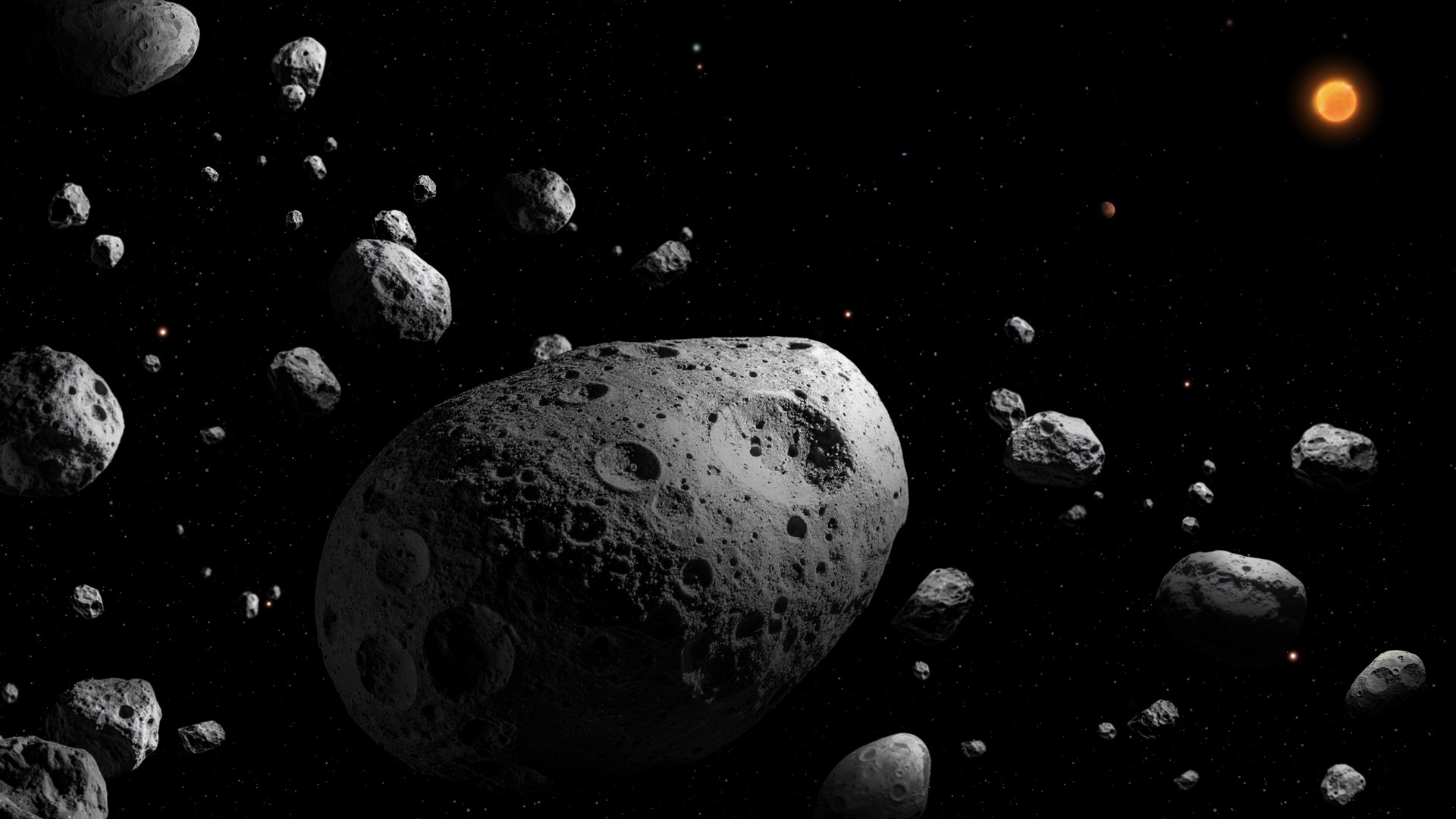

An artist’s conception zeroes in on a main-belt asteroid called 2025 MN45, which makes a full rotation in less than two minutes. (Credit: NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory / NOIRLab / SLAC / AURA / P. Marenfeld)

Astronomers say they’ve found an asteroid that spins faster than other space rocks of its size.

The asteroid, known as 2025 MN45, is nearly half a mile (710 meters) in diameter and makes a full rotation every 1.88 minutes, based on an analysis of data from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. “This is now the fastest-spinning asteroid that we know of, larger than 500 meters,” University of Washington astronomer Sarah Greenstreet said today at the American Astronomical Society’s winter meeting in Phoenix.

Greenstreet, who serves as an assistant astronomer at the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab and heads the Rubin Observatory’s working group for near-Earth objects and interstellar objects, is the lead author of a paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters that describes the discovery and its implications. It’s the first peer-reviewed paper based on data from Rubin’s LSST Camera in Chile.

2025 MN45 is one of more than 2,100 solar system objects that were detected during the observatory’s commissioning phase. Over time, the LSST Camera tracked variations in the light reflected by those objects. Greenstreet and her colleagues analyzed those variations to determine the size, distance, composition and rate of rotation for 76 asteroids, all but one of which are in the main asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. (The other asteroid is a near-Earth object.)

The team found 16 “super-fast rotators” spinning at rates ranging between 13 minutes and 2.2 hours per revolution — plus three “ultra-fast rotators,” including 2025 MN45, that make a full revolution in less than five minutes.

Greenstreet said 2025 MN45 appears to consist of solid rock, as opposed to the “rubble pile” material that most asteroids are thought to be made of.

“We also believe that it’s likely a collisionary fragment of a much larger parent body that, early in the solar system’s history, was heated enough that the material internal to it melted and differentiated,” Greenstreet said. She and her colleagues suggest that the primordial collision blasted 2025 MN45 from the dense core of the parent body and sent it whirling into space.

Astronomers have previously detected fast-spinning asteroids that measure less than 500 meters wide, but this is the first time larger objects have been found with rotational rates that are faster than five minutes per revolution. The Rubin team’s other two ultra-fast rotators have rates of 1.9 minutes and 3.8 minutes.

What would it be like to take a spin on 2025 MN45? Imagine riding on a Ferris wheel — say, the Seattle Great Wheel, which typically makes three revolutions in 10 to 12 minutes. Now make the wheel more than 10 times taller, and make the rotation rate at least twice as fast. It’d feel as if you were going more than 40 mph.

“If you were standing on it, it would probably be quite the ride to be going around on the outside edge of this thing that’s the size of eight football fields,” Greenstreet said.

But the significance of the study goes beyond imagining an extraterrestrial amusement ride.

“This is only the beginning of science for the Rubin Observatory,” Greenstreet said. “We are already seeing that we can study smaller asteroids at farther distances than we’ve ever been able to study before. And being able to study these fast rotators further, we’re going to learn a lot of really crucial information about the internal strength, composition and collisional histories of these primitive solar system bodies that date back to the formation of the solar system.”

The study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, “Lightcurves, Rotation Periods, and Colors for Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s First Asteroid Discoveries,” lists 71 co-authors. Authors from the University of Washington include Greenstreet as well as Zhuofu (Chester) Li, Dmitrii E. Vavilov, Devanshi Singh, Mario Jurić, Željko Ivezić, Joachim Moeyens, Eric C. Bellm, Jacob A. Kurlander, Maria T. Patterson, Nima Sedaghat, Krzysztof Suberlak and Ian S. Sullivan.

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory is jointly funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The University of Washington was one of the founding members of the consortium behind the project, which benefited from early contributions by Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates and software executive Charles Simonyi. The observatory’s Simonyi Survey Telescope was named in honor of Simonyi’s family.

Quelle: GeekWire