29.12.2025

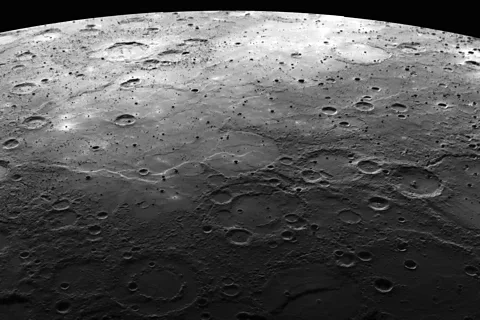

Mercury's surface is scarred with craters and lava flows but below it hides an enormous metal core (Credit: Nasa)

Far smaller and closer to the Sun than it should be, Mercury has long baffled astronomers because it defies much of what we know about planet formation. A new space mission arriving in 2026 might solve the mystery.

At a cursory glance, Mercury might well be the Solar System's dullest planet. Its barren surface has few notable features, there is no evidence of water in its past and the planet's wispy atmosphere is tenuous at best. The likelihood of life being found amidst its scotched craters is non-existent. Yet, look closer and Mercury is a fascinating, improbable world that is shrouded in mystery.

Planetary scientists remain flummoxed by the very existence of the closest planet to our Sun. This peculiar planet is tiny, 20 times less massive than Earth and barely wider than Australia. Yet Mercury is the second densest planet in our Solar System after Earth due to a large, metallic core that accounts for the majority of its mass.

Mercury's orbit – hugging close to our Sun – is also in a weird location that astronomers can't quite explain. All this ties together into one crucial point – we have no idea how Mercury formed. As far as we can tell, the planet simply shouldn't exist.

"It's kind of embarrassing," says Sean Raymond, an expert in planetary formation and dynamics at the University of Bordeaux in France. "There's some key subtlety that we're missing."

The mystery of where Mercury came from, how it formed and why it looks like it does today is one of the grandest mysteries in the Solar System.

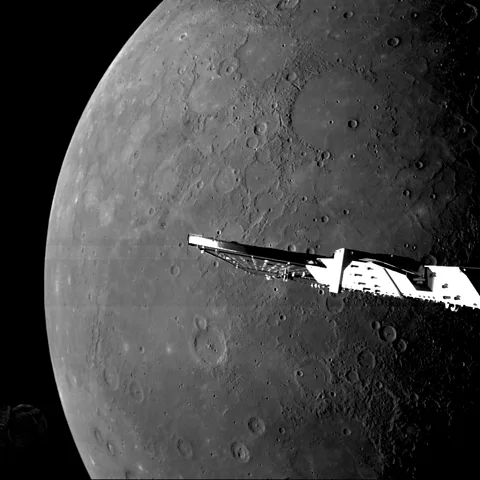

Some answers, however, might be on the horizon. A joint European and Japanese mission called BepiColombo launched in 2018 and is currently on its way to Mercury. The probe will be our first visitor to the planet in more than a decade. When it enters orbit in November 2026, after a thruster problem delayed its journey, one of its key goals is to try and work exactly where Mercury came from.

Working out how Mercury formed is not just important for understanding more about the origins of our own Solar System, but also for studying planets around other stars – exoplanets – too.

"Mercury is probably the closest planet that we have to an exoplanet", due to its unusual formation, says Saverio Cambioni, a planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US. "It's a fascinating world."

Astronomers first realised something was wrong with Mercury after Nasa's Mariner 10 spacecraft flew past the planet three times in 1974 and 1975, which were humanity's first visits to the Solar System's innermost world. Those flybys provided initial gravity measurements of the planet, providing a glimpse inside Mercury for the first time and revealing its bizarre innards.

Earth, Venus and Mars all have iron-rich cores that make up about half of their radius. On Earth, this is separated into a solid inner core and liquid outer core, which churns to produce our world's protective magnetic field. Above is the mantle and then the crust, where we live.

Mercury is completely different. Here the planet's core makes up about 85% of its radius, with only a thin rocky mantle and crust on top. This is what lies behind the planet's incredible density, but why its structure ended up like this isn't entirely clear. "The formation of Mercury is a major problem," says Nicola Tosi, a planetary scientist at the German Aerospace Centre in Berlin. "It's still unclear why Mercury looks like it does."

A later mission to Mercury, Nasa's Messenger mission that orbited the world between 2011 and 2015, only raised more questions. Orbiting just 36 million miles (60 million km) from the Sun, temperatures during the day on Mercury can reach highs of up to 430C (800F) while at night they can plunge as low as -180C (-290F).

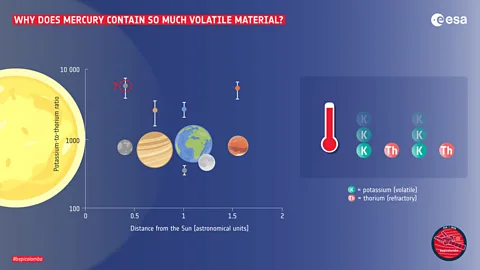

Yet despite these extreme temperatures, Messenger found that Mercury had volatile elements such as potassium and radioactive thorium on its surface, which should have been boiled away by the Sun's radiation long ago. Complex molecules such as chlorine and even water ice trapped in the planet's shadowed polar craters, were also revealed to be hiding on the planet's surface.

Discoveries like this have added to the idea that Mercury does not truly belong in its current home around the Sun. Astronomers have long puzzled over Mercury's position in the Solar System, in a region where we don't think a planet like Mercury could easily form.

We know that solar systems like ours begin as a disk of dust and gas around stars. Slowly, planets carve out gaps in this disk, growing in stature as they sweep up more material. But Mercury is too far away from Venus for this to make sense, based on models of how the planets formed. No matter what parameters dynamicists tweak, they just can't make Mercury as we see it today work out. "It's a pain in the ass," says Raymond. "You get zero Mercuries."

Astronomers have spent years refining models and testing ideas for how Mercury might have formed, and there are a few leading scenarios. One of the most discussed is the idea that Mercury was once much bigger, perhaps twice its current bulk and nearly the size of Mars. It may also have been orbiting farther away from the Sun.

This is supported by the potassium and thorium levels detected on Mercury, which are much more similar to those on Mars, a planet that formed further from the Sun.

The theory is that at some point in its first 10 million years of existence, this proto-Mercury was hit by a massive object, perhaps another Mars-sized planet. The collision stripped the planet of its outer layers – the crust and mantle – leaving just the dense iron-rich core that forms most of the world we see today.

ESA

ESAThis explanation is perhaps the one most strongly favoured by astronomers at present, says Alessandro Morbidelli, a planetary dynamicist at the Côte d'Azur Observatory in Nice, France. "The general interpretation is that Mercury suffered a giant impact that removed most of the mantle," he says.

It would have needed to be a grazing impact, so as not to destroy Mercury completely. However, while impacts were common in the early Solar System, stripping so much material from Mercury would require a violent smash-up at speeds of more than 224,000mph (100km/s) says Cambioni, a scenario that is thought to be unlikely because most objects would have been moving around the Sun in similar directions with similar speeds relative to each other, like cars on a roundabout.

Such an impact should also have stripped Mercury of its volatile elements, including thorium, making Messenger's detection of them equally puzzling. How would they have survived such an explosive event?

Even without an impact, it's not clear how these elements could still be on Mercury. "Something that close to the Sun shouldn't be rich in volatiles," says David Rothery, a planetary geoscientist at The Open University in the UK who co-leads BepiColombo's Mercury Imaging X-ray Spectrometer (MIXS) instrument that will study the planet's volatiles. "So did Mercury begin farther out, or did the things which aggregated to form Mercury begin farther out?"

Maybe Mercury didn't suffer an impact, but was the impactor itself, crashing into another world – like Venus – before ending up in its current position. It's a promising idea because it might be easier to strip off Mercury's mantle in such a hit-and-run collision. "It's easier to explain Mercury if it was the impactor and not the impacted," says Olivier Namur, a planetary geologist at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium.

It wouldn't have been the only planet-sized cannonball rocketing around the early Solar System. Our own Moon is thought to have formed when a Mars-sized object called Theia collided with the early Earth, carving off a huge chunk.

Nasa

NasaIn any of the impact scenarios for Mercury, it's not clear why the rocky debris thrown into space wouldn't have fallen back onto the planet or created its own moons (Mercury has no moons).

One possibility might be a process called collisional grinding, where the ejected material from Mercury was broken down to dust that was then blown away by the barrage of the solar wind. "Collisional grinding is the debris itself grinding down into smaller and smaller chunks," says Jennifer Scora, a planetary formation expert at the University of Toronto in Canada. "You end up with a Mercury that is smaller and also more dense." But the rate of grinding required is high for this to work, perhaps more than we expect to happen, she says.

Another scenario is that there was no giant impact at all, but instead Mercury really did form from material nearer the Sun that was more iron-rich. In this situation, favoured by Anders Johansen, a planet formation expert at Lund University in Sweden, Mercury formed in a region of the Solar System that was much hotter than the other planets, with outbursts from the young Sun essentially evaporating most of the lighter dust at Mercury's position and leaving only heavier iron-rich material to coalesce together. "Then you could form an iron-rich planet," says Johansen.

Again there are problems. If this were true, why would Mercury have stopped growing at its present size, rather than continuing to accumulate iron-rich material? "There will be lots of material around," says Johansen, so it's unsure why we would have been left with the small planet we see today.

Around other stars we do see evidence for larger versions of Mercury, known as Super Mercuries, iron-rich dense planets more massive and bigger than Earth but still with a large iron core. The reason we haven't yet discovered any planets the size of Mercury is because they are simply too small to spot against the glare and gravitational heft of their host star.

Observations of other stars suggest Super Mercuries might be quite common in our galaxy, says Cambioni, accounting for perhaps 10 to 20% of all planets out there. That's a bit of a problem because, like Mercury, we don't know how they form – they are too big to form via any collision scenario, for example. "They are uncomfortably common," says Cambioni.

There is another theory for how Mercury came to be – one where the inner planets didn't form where they are now, but instead moved around a bit. In one model of the Solar System, the inner planets of Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars might have formed in two distinct rings of material around the Sun. Earth and Venus formed alongside Mercury in the inner ring, before they "migrated away and left Mercury behind", says Raymond, because of its lower mass.

Modelling by Matt Clement, a planetary dynamicist at the University of Oxford in the UK, suggests the rocky planets could have all formed much closer to the Sun, within Mercury's current orbit, before moving outwards. "Mercury gets kicked out of the action and runs out of material," he says. The idea doesn't quite solve why Mercury would have such a large core, unless it moved into a region of the Solar System that was richer in iron, but it does solve why the planet is the size it is and its distance from Venus. "I think you need migration," says Clement.

There are some more unusual ideas too. What if Mercury isn't a rocky planet per se, but the naked core of a gas giant planet like Jupiter that had its atmosphere ripped away? While such an idea has been touted, Cambioni thinks it is unlikely. "It is very hard to remove the atmosphere of a Jupiter-sized planet," he says, due to their immense gravity.

All of this provides astronomers with many clues but no consensus as to how Mercury formed. BepiColombo may provide some answers.

When the mission – it is in fact two spacecraft operated by the European Space Agency (Esa) and Japanese Space Agency (Jaxa) joined together – enters orbit around Mercury, the two vessels will separate. They will then use their instruments to map the composition of Mercury's surface while also studying the planet's gravity and weak magnetic field, among other observations.

"BepiColombo will perform additional measurements that can tell us about the origin of the planet," says Tosi. Of particular interest will be discovering what the surface and the subsurface of the planet are made of. "Knowing that composition places constraints on the formation of the planet," says Tosi.

If Mercury was once much larger but was then stripped away, it should have created a temporarily molten mantle, a vast ocean of magma that we could see evidence of today. "This solidifies in a certain way," says Tosi, evidence of which BepiColombo can look for.

Early images beamed back by the spacecraft as it made a flyby of Mercury earlier this year have yet to reveal evidence of this ancient magma ocean. But they have shown a planet surface scarred with impact craters and streaked from ancient lava flows. The remnants of a lava flood from a bout 3.7 billion years ago could also be seen, where it had hardened into large expanses of "smooth" surface and filled in older craters. Although much more recent than the magma ocean that might have existed, distinctive wrinkles in the smooth surface indicate that the plant has since been contracting dramatically as it has cooled down over billions of years.

The spacecraft's gravity measurements, tracking how much the planet deforms in response to the Sun's gravity by bouncing a laser off its surface, should also give scientists a better understanding of the structure of the core, another important piece in the planet's history. "Knowing the composition of the core will also help to reconstruct where Mercury comes from," says Tosi.

BepiColombo should also reveal more about the volatile elements on Mercury, which remain confusing. "We know Mercury is rich in volatiles but we don't know what all the volatiles are," says Rothery.

It could also help to solve other mysteries about mercury – such as why its crater-splattered surface is so dark. The planet only reflects around two-thirds as much light as the Earth's Moon, suggesting there may be a layer of dark material such as graphite blanketing the surface.

ESA/ BepiColombo/ MTM

ESA/ BepiColombo/ MTMTo truly understand the origin of Mercury, however, scientists dream of one day landing on the planet – something that was originally part of the BepiColombo proposal but scrapped early-on due to cost and complexity– and maybe even returning samples to Earth. "What we really want is a sample of Mercury," says Rothery, which would allow us to pick apart exactly what the planet is made of.

No such mission is planned for the foreseeable future but there have been some proposals. In lieu of a lander, "our best hope is to find a meteorite that originated from Mercury", says Rothery, something that is not beyond the realms of possibility. Hundreds of meteorites from Mars have been found on Earth, but none definitively from Mercury (or Venus, for that matter).

There has been a suggestion that a rare class of meteorites on Earth, called aubrites, are pieces of the supposed proto-Mercury, the larger initial planet that was hit by another body. The idea remains "wild speculation" says Morbidelli, but alluring nonetheless because of their similar chemistry and mineralogy to what we think proto-Mercury would have looked like. (Read about geological "analogues" for Mercury's rocks found here on Earth.)

Camille Cartier, a petrologist at the University of Lorraine in France, is leading a study of aubrites to investigate this possibility over the next couple of years. "We have a super collection" of aubrite meteorites, she says, with her team collecting samples from about 20 different aubrites. Now they will study them in a laboratory to investigate whether they truly are pieces of Mercury.

"We should have strong evidence in favour or not of this hypothesis," says Cartier.

At stake for understanding Mercury's formation is getting to grips with planet formation itself. Was the planet just a complete fluke, the result of a chance high-speed collision in our Solar System, or something more ubiquitous? "Maybe Mercury is not such a rare object and is a natural result of planet formation," says Tosi.

For now the puzzle of Mercury's origin endures. Why do we have this weirdly small and super-metallic planet in our Solar System, and do other stars have Mercuries too?

On its surface Mercury might be a pockmarked grey world devoid of obvious interest, but deep down this enigmatic world might just be one of the most fascinating places in the Solar System.

"It's possible Mercury is just an unlikely planet," says Scora, one that in most timelines simply shouldn't exist – but in ours it does.

Quelle: BBC