29.12.2025

Rendezvous with Starburst; the fine control electromagnetic propulsion promises could be used to bring objects together in space.SUPPLIED

The propulsion system that Auckland company Zenno has created can produce a force that could be able to steer larger, much more expensive geo-stationary satellites in space. That’s made it one of the country’s hottest start-ups, Tom Pullar-Strecker reports.

Auckland company Zenno has spent eight years developing a propulsion system that generates a force co-founder Sebastian Wieczorek says could be reasonably compared with that you would get from pushing something with your little finger.

So why is it one of the country’s hottest start-ups, having so far raised $29 million from investors in New Zealand and overseas?

The answer is that it can produce that ‘finger-force’ in space, where resistance is next to zero and it could be all that is needed to spin a one-tonne satellite on its axis, or perhaps nudge several rocket-loads of components together to self-assemble into a space station.

“The fields that we found from the units we’ve been testing are of the order of what you’d find in an MRI machine” in a hospital, Wieczorek says.

The power source that is usually used to move satellites is a propellant expelled from a nozzle. Every force has an equal and opposite reaction, so push the propellent out in one direction and the satellite will move in the other — even in space.

But fine control is difficult using such a crude technique and satellites can’t be refuelled in orbit, so once the propellant has all been used up, it’s game over, as it was earlier this year for an ageing Optus satellite used to deliver Sky TV to Kiwis.

The “engine” Zenno has developed is an electromagnetic field generated by a wire coil that could in theory be powered indefinitely by the solar panels on a satellite and energy from the sun.

One magnet on its own isn’t enough to move anything, but if there is another magnet that it can push and pull against, then that is a different matter.

And fortunately there is another force in space for Zenno’s field-generator to work with; that is the Earth’s own much weaker electromagnetic field, generated by molten iron and nickel slopping about in the planet's outer core.

Wieczorek says Zenno isn’t the only company to harness the power of electric fields in space. That has already been achieved in some small, low-Earth-orbit satellites that rattle around the planet each day delivering services such as Starlink broadband.

But by using superconductor technology, Zenno has been able to create electric fields which — while still generating tiny forces in conventional terms — are much more powerful, he says.

The significance of that is they can be used to steer larger, much more expensive geo-stationary satellites that are designed to sit in a fixed position over a country and deliver services such as satellite TV, GPS signals, and weather forecasting.

In order to stay in sync with the Earth’s orbit, geo-stationary satellites need to be positioned further out in space, where the Earth’s gravitational force is weaker, but where its magnetic field is also about 100 times less strong — making the extra power of the magnetic field it is interacting with all-important.

Zenno, which now employs 19 staff, has had to crack some difficult challenges along the way.

While its own satellite-based systems generates a stable electromagnetic field, the Earth’s field is in a constant state of flux, making the “push and pull” that is generated by the interplay between the two hard to predict.

“What we do is we fly a little device called a magnetometer on board, which measures the magnetic field at each moment, so we don't have to rely on any models and can deal with that data as it comes in,” Wieczorek says.

Zenno now appears on the edge of commercialisation.

Its systems have been tested in space and late next year Seattle-based Portal Space Systems will use Zenno’s flagship 10kg “Supertorquer” field-generator to help steer a new high-manoeuvrable satellite it has been developing for national security and commercial use.

Wieczorek says he can’t disclose the commercial terms of the deal, for example whether Portal may be Zenno’s first paying customer, but describes the partnership as ground-breaking.

Zenno isn’t currently promoting its technology as a complete alternative to propellant-based boosters.

For the time being at least, Wieczorek believes propellent will continue to be used to manage large orbital manoeuvres, such as keeping them the right distance away from the Earth and sometimes moving them across continents.

But he believes Zenno’s technology will come into its own keeping satellites — and therefore the instruments they carry — pointing in the right direction, and perhaps in satellite self-assembly.

“Right now, the market is very hot on complex manufacturing in space.”

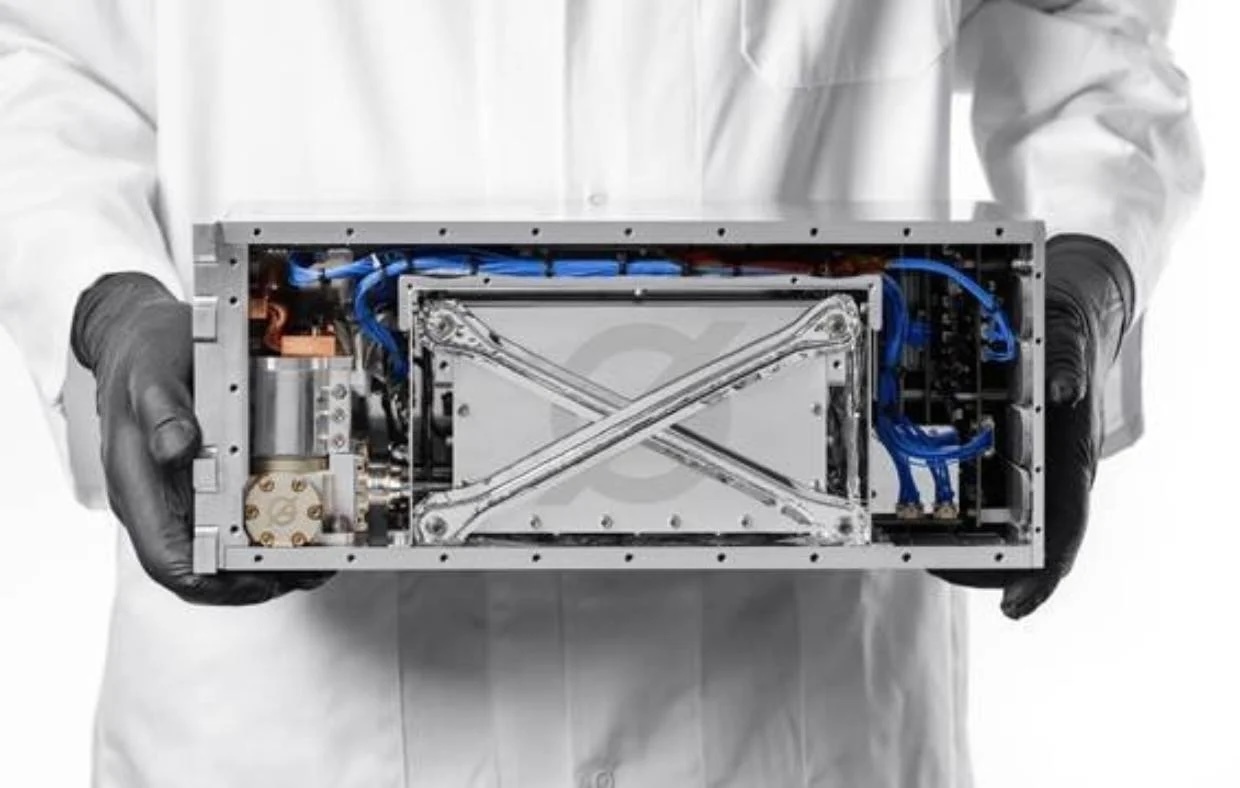

Zenno’s Z01 superconducting electro-magnetic field generator is one half of what’s needed to turn energy from the sun into the power to move objects in space.

There are also situations where it would be useful to be able to delicately steer groups of satellites so they were able to orbit in close proximity and mimic a large, single platform, such as a giant telescope.

One goal of Portal Space Systems’ Starburst mission is to demonstrate the Seattle-based firm’s ability to “rendezvous” its satellite with other objects in space.

Wieczorek says he is particularly excited by the potential to use the electromagnetic fields Zenno’s conductors generate to protect spacecraft and crew they might carry from solar radiation, in the same way that the Earth’s natural field protects people from many of the harmful effects of the sun.

That could make longer-distance space travel more viable, he says.

“That's our long term vision and we think that's the most impactful thing we can do to assist life in space.”

“Our best approach to this problem currently is just to throw more material at it, so currently in the International Space Station they have a thick wall of material to physically stop the rays from coming in, but obviously it costs a lot of money to send mass into space. If we could create a radiation shield, we could save companies a lot of money.”

Quelle: ThePost