25.07.2025

Astronomers find signs of complex organic molecules – precursors to sugars and amino acids – in a planet-forming disc.

To the point

- First tentative detection of prebiotic molecules in a planet-forming disc: In the young V883 Orionis system, ALMA observations have revealed signatures of complex organic compounds such as ethylene glycol and glycolonitrile – potential precursors to sugars and amino acids.

- Chemical evolution begins before planets are formed: The findings suggest that protoplanetary discs inherit and further develop complex molecules from earlier evolutionary stages, rather than forming them anew.

- Evidence for universal processes in the origin of biological molecules: The building blocks of life may not be limited to local conditions but could form widely throughout the Universe under suitable circumstances.

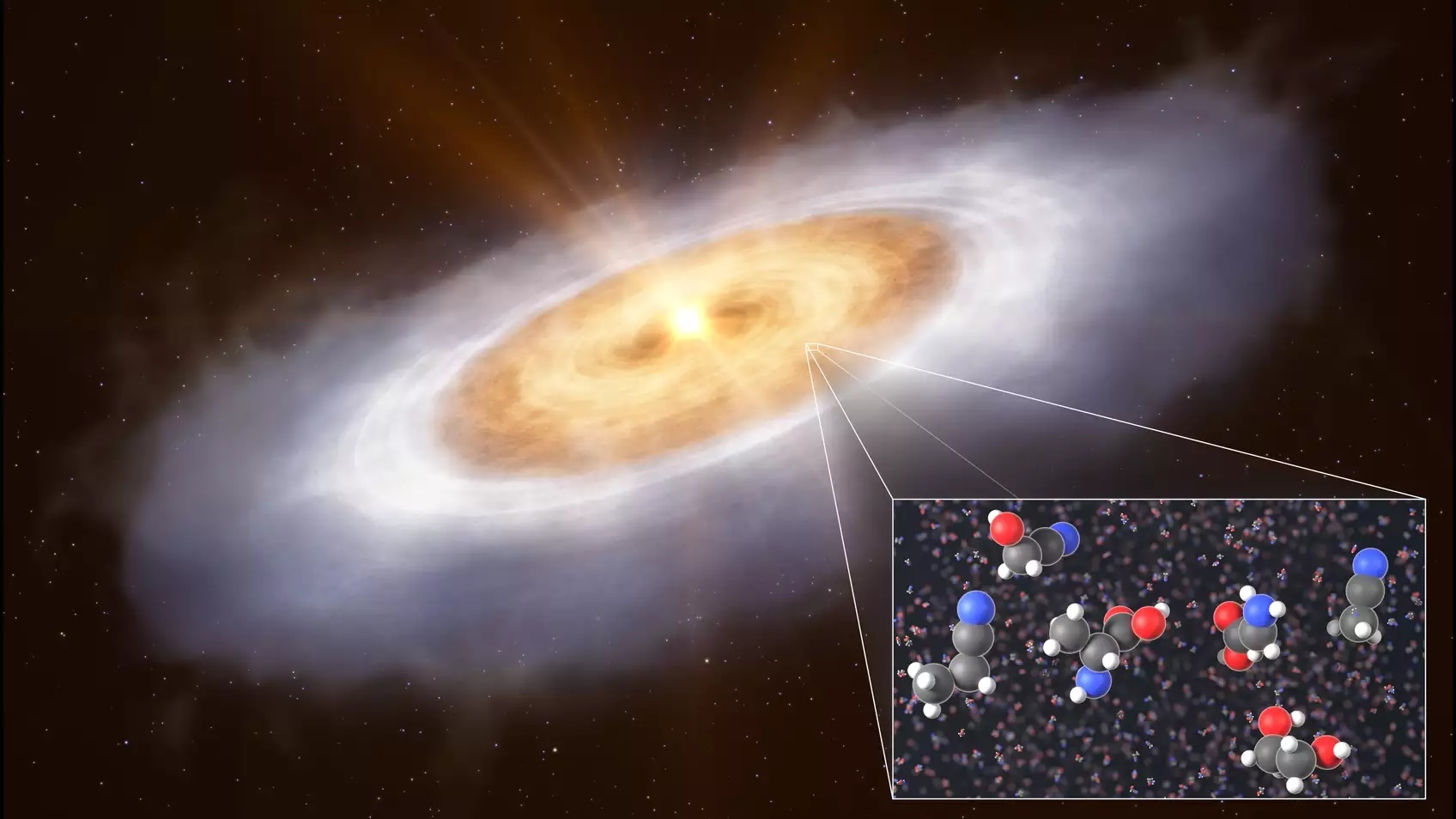

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a team of astronomers led by Abubakar Fadul from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) has discovered complex organic molecules – including the first tentative detection of ethylene glycol and glycolonitrile – in the protoplanetary disc of the outbursting protostar V883 Orionis. These compounds are considered precursors to the building blocks of life. Comparing different cosmic environments reveals that the abundance and complexity of such molecules increase from star-forming regions to fully evolved planetary systems. This suggests that the seeds of life are assembled in space and widespread.

Astronomers have discovered complex organic molecules (COMs) in various locations associated with planet and star formation before. COMs are molecules with more than five atoms, at least one of which is carbon. Many of them are considered building blocks of life, such as amino acids and nucleic acids or their precursors. The discovery of 17 COMs in the protoplanetary disc of V883 Orionis, including ethylene glycol and glycolonitrile, provides a long-sought puzzle piece in the evolution of such molecules between the stages preceding and following the formation of stars and their planet-forming discs. Glycolonitrile is a precursor of the amino acids glycine and alanine, as well as the nucleobase adenine. The findings were published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters today.

The assembly of prebiotic molecules begins in interstellar space

The transition from a cold protostar to a young star surrounded by a disc of dust and gas is accompanied by a violent phase of shocked gas, intense radiation and rapid gas ejection. Such energetic processes might destroy most of the complex chemistry assembled during the previous stages. Therefore, scientists had laid out a so-called ‘reset’ scenario, in which most of the chemical compounds required to evolve into life would have to be reproduced in circumstellar discs while forming comets, asteroids, and planets.

“Now it appears the opposite is true,” MPIA scientist and co-author Kamber Schwarz points out. “Our results suggest that protoplanetary discs inherit complex molecules from earlier stages, and the formation of complex molecules can continue during the protoplanetary disc stage.” Indeed, the period between the energetic protostellar phase and the establishment of a protoplanetary disk would, on its own, be too short for COMs to form in detectable amounts.

As a result, the conditions that predefine biological processes may be widespread rather than being restricted to individual planetary systems.

Astronomers have found the simplest organic molecules, such as methanol, in dense regions of dust and gas that predate the formation of stars. Under favourable conditions, they may even contain complex compounds comprising ethylene glycol, one of the species now discovered in V883 Orionis. “We recently found ethylene glycol could form by UV irradiation of ethanolamine, a molecule that was recently discovered in space,” adds Tushar Suhasaria, a co-author and the head of MPIA’s Origins of Life Lab. “This finding supports the idea that ethylene glycol could form in those environments but also in later stages of molecular evolution, where UV irradiation is dominant.”

More evolved agents crucial to biology, such as amino acids, sugars, and nucleobases that make up DNA and RNA, are present in asteroids, meteorites, and comets within the Solar System.

Buried in ice – resurfaced by stars

The chemical reactions that synthesize those COMs occur under cold conditions, preferably on icy dust grains that later coagulate to form larger objects. Hidden in those mixtures of rock, dust, and ice, they usually remain undetected. Accessing those molecules is only possible either by digging for them with space probes or external heating, which evaporates the ice.

In the Solar System, the Sun heats comets, resulting in impressive tails of gas and dust, or comas, essentially gaseous envelopes that surround the cometary nuclei. This way, spectroscopy – the rainbow-like dissection of light – may pick up the emissions of freed molecules. Those spectral fingerprints help astronomers to identify the molecules previously buried in ice.

A similar heating process is occurring in the V883 Orionis system. The central star is still growing by accumulating gas from the surrounding disc until it eventually ignites the fusion fire in its core. During those growth periods, the infalling gas heats up and produces intense outbursts of radiation. “These outbursts are strong enough to heat the surrounding disc as far as otherwise icy environments, releasing the chemicals we have detected,” explains Fadul.

“Complex molecules, including ethylene glycol and glycolonitrile, radiate at radio frequencies. ALMA is perfectly suited to detect those signals,” says Schwarz. The MPIA astronomers were awarded access to this radio interferometer through the European Southern Observatory (ESO), which operates it in the Chilean Atacama Desert at an altitude of 5,000 metres. ALMA enabled the astronomers to pinpoint the V883 Orionis system and search for faint spectral signatures, which ultimately led to the detections.

Further challenges ahead

“While this result is exciting, we still haven't disentangled all the signatures we found in our spectra,” says Schwarz. “Higher resolution data will confirm the detections of ethylene glycol and glycolonitril and maybe even reveal more complex chemicals we simply haven't identified yet.”

“Perhaps we also need to look at other regions of the electromagnetic spectrum to find even more evolved molecules,” Fadul points out. “Who knows what else we might discover?”

Additional information

The MPIA team involved in this study consisted of Abubakar Fadul (now at the University of Duisburg-Essen), Kamber Schwarz, and Tushar Suhasaria.

Other researchers were Jenny K. Calahan (Center for Astrophysics — Harvard & Smithsonian, Cambridge, USA), Jane Huang (Department of Astronomy, Columbia University, New York, USA), and Merel L. R. van ’t Hoff (Department of Physics and Astronomy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, USA).

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of the European Southern Observatory (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) in Taiwan and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI). ALMA construction and operations are led by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), on behalf of North America; and by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.

+++

Die Evolution des Lebens beginnt vermutlich im Weltall

Astronomen finden Hinweise auf komplexe organische Moleküle – Vorstufen von Zuckern und Aminosäuren – in einer planetenbildenden Scheibe.

Auf den Punkt gebracht

- Erste Hinweise auf präbiotische Moleküle in einer planetenbildenden Scheibe: Im jungen Sternsystem V883 Orionis konnten mit ALMA erste Hinweise auf komplexe organische Verbindungen wie Ethylenglykol und Glykolnitril identifiziert werden – mögliche Vorläufer von Zuckern und Aminosäuren.

- Chemische Entwicklung beginnt vor der Planetenentstehung: Die Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass protoplanetare Scheiben komplexe Moleküle aus früheren Phasen übernehmen und weiterentwickeln, anstatt sie vollständig neu zu bilden.

- Hinweise auf universelle Prozesse bei der Entstehung biologischer Moleküle: Die Bausteine des Lebens entstehen offenbar nicht nur lokal, sondern könnten unter geeigneten Bedingungen im gesamten Universum gebildet werden.

Ein Forschungsteam unter der Leitung von Abubakar Fadul vom Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie (MPIA) hat mit dem ALMA-Teleskop komplexe organische Moleküle in der protoplanetaren Scheibe des Protosterns V883 Orionis entdeckt – darunter wahrscheinlich erstmals Ethylenglykol und Glykolnitril. Diese Verbindungen gelten als Vorstufen der Bausteine des Lebens. Ein Vergleich verschiedener kosmischer Umgebungen zeigt, dass sowohl die Häufigkeit als auch die Komplexität solcher Moleküle von Sternentstehungsgebieten hin zu Planetensystemen zunimmt. Dies deutet darauf hin, dass die Bausteine des Lebens bereits im Weltraum gebildet werden und weitverbreitet sind. Die Ergebnisse wurden heute in den Astrophysical Journal Letters veröffentlicht.

Komplexe organische Moleküle (COMs; complex organic molecules) wurden bereits an verschiedenen Orten nachgewiesen, die mit der Entstehung von Sternen und Planeten in Verbindung stehen. COMs bestehen aus mehr als fünf Atomen, darunter mindestens ein Kohlenstoffatom. Viele von ihnen gelten als Vorläufer wichtiger biologischer Verbindungen, etwa von Aminosäuren und Nukleinsäuren. Die Entdeckung von 17 COMs in der protoplanetaren Scheibe des Protosterns V883 Orionis schließt eine lang bestehende Lücke im Verständnis der chemischen Entwicklung dieser Moleküle – von der Zeit vor der Sternentstehung bis zur Bildung planetenbildender Scheiben. Erstmals konnten dabei auch die Signaturen von Ethylenglykol und Glykolnitril nachgewiesen werden. Aus Glykolnitril können sich die Aminosäuren Glycin und Alanin sowie die Nukleinbase Adenin bilden.

Die Entstehung präbiotischer Moleküle beginnt im interstellaren Raum

Der Übergang von einem kalten Protostern zu einem jungen Stern, der von einer Scheibe aus Staub und Gas umgeben ist, ist durch heftige Phasen mit Schockwellen, intensiver Strahlung und gewaltigen Gasausstößen gekennzeichnet. Bislang wurde angenommen, dass diese extremen Bedingungen die zuvor gebildeten chemischen Verbindungen weitgehend zerstören. Gemäß dieses sogenannten „Reset“-Szenarios müssten die meisten chemischen Stoffe, die später zu lebenswichtigen Molekülen werden, erst in protoplanetaren Scheiben neu entstehen – während der Bildung von Kometen, Asteroiden und Planeten.

„Nun scheint aber genau das Gegenteil der Fall zu sein“, erläutert Kamber Schwarz, MPIA-Wissenschaftlerin und Mitautorin der Studie. „Protoplanetare Scheiben übernehmen komplexe Moleküle aus früheren Stadien, und ihre chemische Evolution setzt sich während der Scheibenphase fort.“ Tatsächlich wäre die Zeit zwischen der energiereichen Protosternphase und der Entstehung einer stabilen protoplanetaren Scheibe zu kurz, um komplexe organische Moleküle in nachweisbaren Mengen neu zu bilden. Das bedeutet, dass die chemischen Voraussetzungen für biologische Prozesse nicht nur unter lokalen Bedingungen in einzelnen Planetensystemen vorliegen, sondern weitverbreitet sein könnten.

Bereits in dichten Gas- und Staubwolken, die Sternen vorausgehen, konnten einfache organische Moleküle wie Methanol nachgewiesen werden. Unter günstigen Bedingungen entstehen dort sogar komplexere Verbindungen wie Ethylenglykol – eine der nun in V883 Orionis entdeckten Substanzen. „Unsere Forschung zeigt, dass Ethylenglykol durch Bestrahlung mit UV-Licht aus Ethanolamin entstehen kann – einem Molekül, das kürzlich im Weltraum entdeckt wurde“, erklärt Tushar Suhasaria, Mitautor der Studie und Leiter des MPIA-Labors zur Erforschung der Ursprünge des Lebens. „Dieser Befund lässt vermuten, dass Ethylenglykol nicht nur in frühen Sternentstehungsgebieten gebildet wird, sondern auch in späteren Entwicklungsstufen, wenn UV-Strahlung eine dominierende Rolle spielt.“

Noch komplexere organische Moleküle, die für biologische Prozesse essenziell sind – darunter Aminosäuren, Zucker und Nukleobasen, die DNA und RNA bilden – wurden bereits in Asteroiden, Meteoriten und Kometen unseres Sonnensystems nachgewiesen.

Im Eis verborgen – von Sternen wieder freigelegt

Die chemischen Reaktionen, die zur Bildung komplexer organischer Moleküle führen, finden bevorzugt unter extrem kalten Bedingungen statt – idealerweise auf eisbedeckten Staubpartikeln, die sich allmählich zu größeren Himmelskörpern verklumpen. Eingebettet in eine Mischung aus Gestein, Staub und Eis bleiben diese Moleküle meist verborgen. Diese Moleküle aufzuspüren ist nur möglich, indem man sie mit Raumsonden freilegt oder das Eis durch Wärme von außen verdampft.

In unserem Sonnensystem geschieht dies, wenn etwa die Sonne einen Kometen erwärmt. Dadurch bildet sich ein eindrucksvoller Gas- und Staubschweif und eine Koma, eine Hülle aus Gas, die den Kometenkern umgibt. Freigesetzte Moleküle lassen sich so durch Spektroskopie – die regenbogenartige Zerlegung von Licht – nachweisen. Diese spektralen Fingerabdrücke helfen Astronomen, die zuvor im Eis verborgenen Moleküle zu bestimmen.

Ein ähnlicher Prozess spielt sich auch im System V883 Orionis ab. Der zentrale Protostern wächst weiter, indem er Gas aus der umgebenden Scheibe ansammelt. In bestimmten Wachstumsphasen heizt sich das einströmende Material stark auf und löst heftige Strahlungsausbrüche aus. „Diese Energie reicht aus, um selbst weit entfernte, eisige Regionen der Scheibe zu erwärmen und die dort verborgenen Moleküle freizusetzen“, erklärt Fadul.

„Komplexe Moleküle wie Ethylenglykol und Glykolnitril senden Radiowellen aus. ALMA ist daher ideal geeignet, um diese Signale zu empfangen“, ergänzt Schwarz. Die MPIA-Forschenden erhielten Beobachtungszeit am ALMA-Radiointerferometer über die Europäische Südsternwarte (ESO), die das Observatorium in der chilenischen Atacama-Wüste auf 5.000 Metern Höhe betreibt. Mit ALMA gelang es dem Team, das System V883 Orionis exakt anzuvisieren und die schwachen Spektralsignaturen nachzuweisen, die die aktuelle Entdeckung ermöglichten.

Weitere Herausforderungen liegen vor uns

„Dieses Ergebnis ist zwar aufregend, aber wir haben bisher nicht alle Signaturen entschlüsselt, die wir in unseren Spektren gefunden haben“, sagt Schwarz. „Daten mit höherer Auflösung werden die Nachweise von Ethylenglykol und Glykolnitril bestätigen. Vielleicht sind darin noch komplexere Chemikalien verborgen, die wir bisher nicht identifiziert haben.“

„Womöglich müssen wir auch andere Bereiche des elektromagnetischen Spektrums untersuchen, um noch längere Moleküle zu finden“, unterstreicht Fadul. „Wer weiß, was wir noch alles finden werden?“

Hintergrundinformation

Das MPIA-Team, das an dieser Studie beteiligt war, bestand aus Abubakar Fadul (jetzt an der Universität Duisburg-Essen), Kamber Schwarz und Tushar Suhasaria.

Weitere Forschende waren Jenny K. Calahan (Center for Astrophysics — Harvard & Smithsonian, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), Jane Huang (Department of Astronomy, Columbia University, New York, USA) und Merel L. R. van 't Hoff (Department of Physics and Astronomy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, USA).

Das Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) ist eine internationale astronomische Einrichtung, die gemeinsam von der ESO, der US-amerikanischen National Science Foundation (NSF) der USA und den japanischen National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) in Kooperation mit der Republik Chile betrieben wird. Getragen wird ALMA von der ESO im Namen ihrer Mitgliedsländer, von der NSF in Zusammenarbeit mit dem kanadischen National Research Council (NRC), dem Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) und NINS in Kooperation mit der Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan sowie dem Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI). Bei Entwicklung, Aufbau und Betrieb ist die ESO federführend für den europäischen Beitrag, das National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), das seinerseits von Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI) betrieben wird, für den nordamerikanischen Beitrag und das National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) für den ostasiatischen Beitrag. Dem Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) obliegt die übergreifende Projektleitung für den Aufbau, die Inbetriebnahme und den Beobachtungsbetrieb von ALMA.

Quelle: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft