Higher latitudes on the moon with slopes facing the poles "are not only scientifically interesting but also pose less technical challenges for exploration in comparison with regions closer to the poles of the moon."

An artist's depiction of the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter studying the moon. (Image credit: NASA)

Future astronauts traveling to the moon may have easier access to life-sustaining water and extractable ice than previously thought, according to new research.

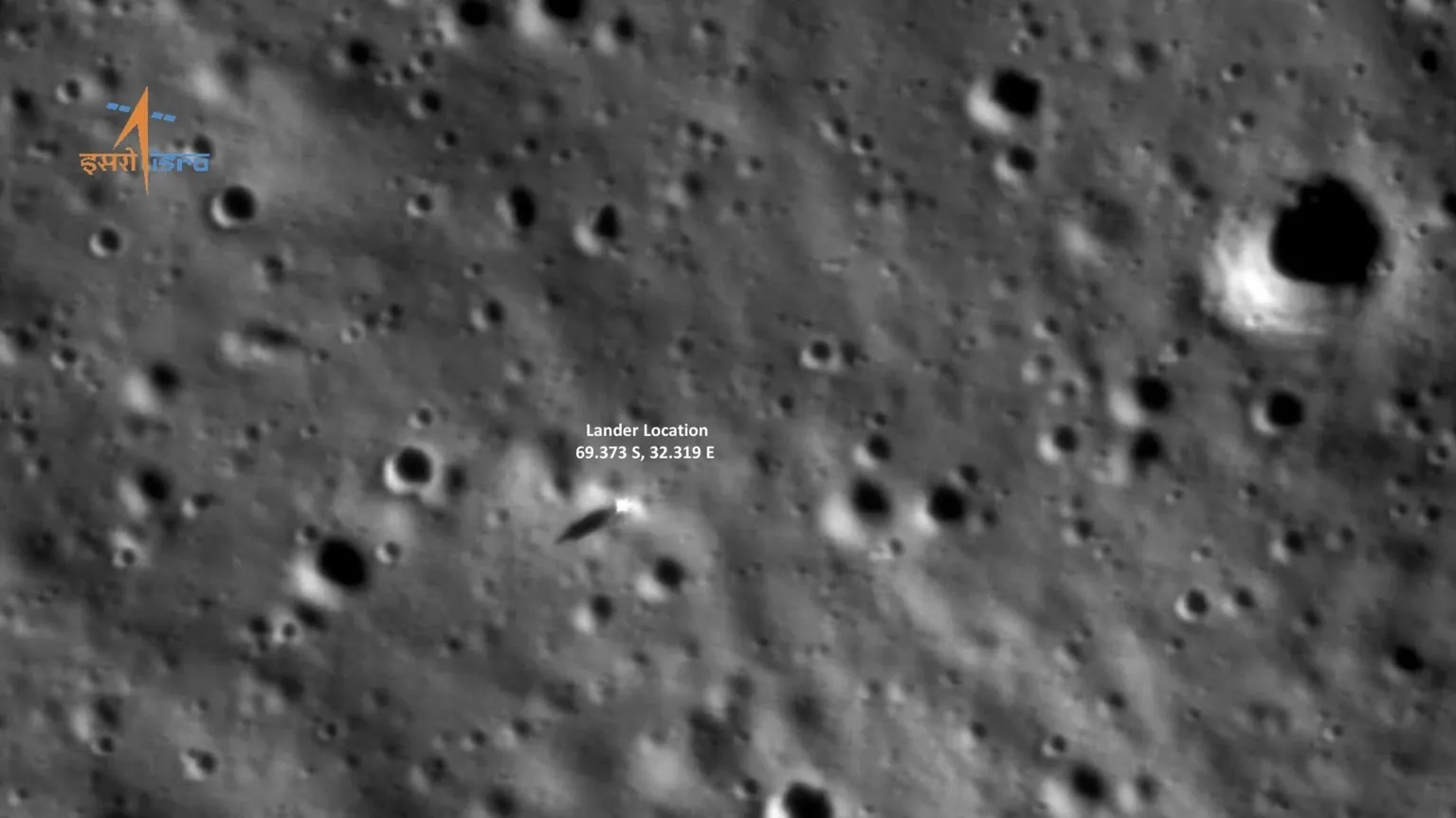

A team of scientists led by Durga Prasad of the Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad analyzed lunar temperature data collected on site by India's Chandrayaan-3 mission, which landed near the moon's south pole in August 2023. The researchers found that temperatures at the spacecraft's landing site fluctuated dramatically, even among areas that are very close to each other.

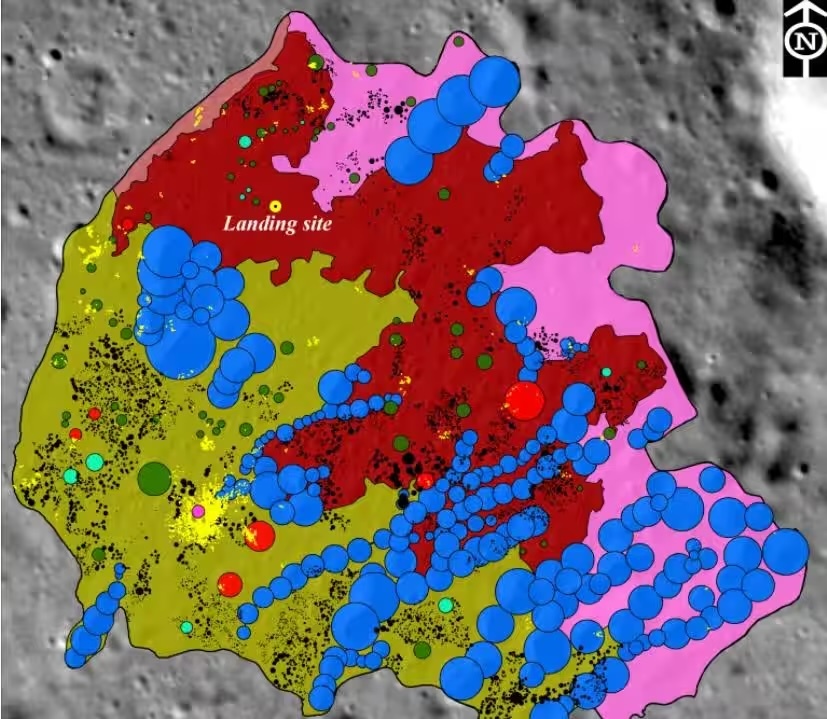

To better understand these temperature swings, the researchers plugged this data into a computer model they fine-tuned to match the spacecraft's landing conditions, including local topography and illumination. The results suggest higher latitudes on the moon with slopes that face its poles share conditions similar to those at Chandrayaan-3's landing site. These regions typically receive less intense solar energy, which leads to cooler surface temperatures that could allow for the accumulation of ice at relatively shallow depths. This means such lunar areas would present fewer technical challenges for accessing local resources compared to the more extreme conditions at the moon's crater-riddled poles, the researchers say.

The findings hold significance for agencies planning long-term crewed missions to the moon's south pole, such as NASA with its Artemis program. If ice can be found and harnessed on the moon, it could reduce astronauts' reliance on Earth-based supplies, making missions more sustainable and cost-effective. Water extracted from ice could serve multiple purposes for astronauts, not only as drinking water but also for producing rocket fuel by splitting water molecules into their constituent parts — oxygen and hydrogen.

For decades, however, the only direct measurements of the moon's surface temperature were taken during the Apollo 15 and 17 missions in the 1970s, both of which landed near the moon's equator — far from the proposed sites for future polar missions.

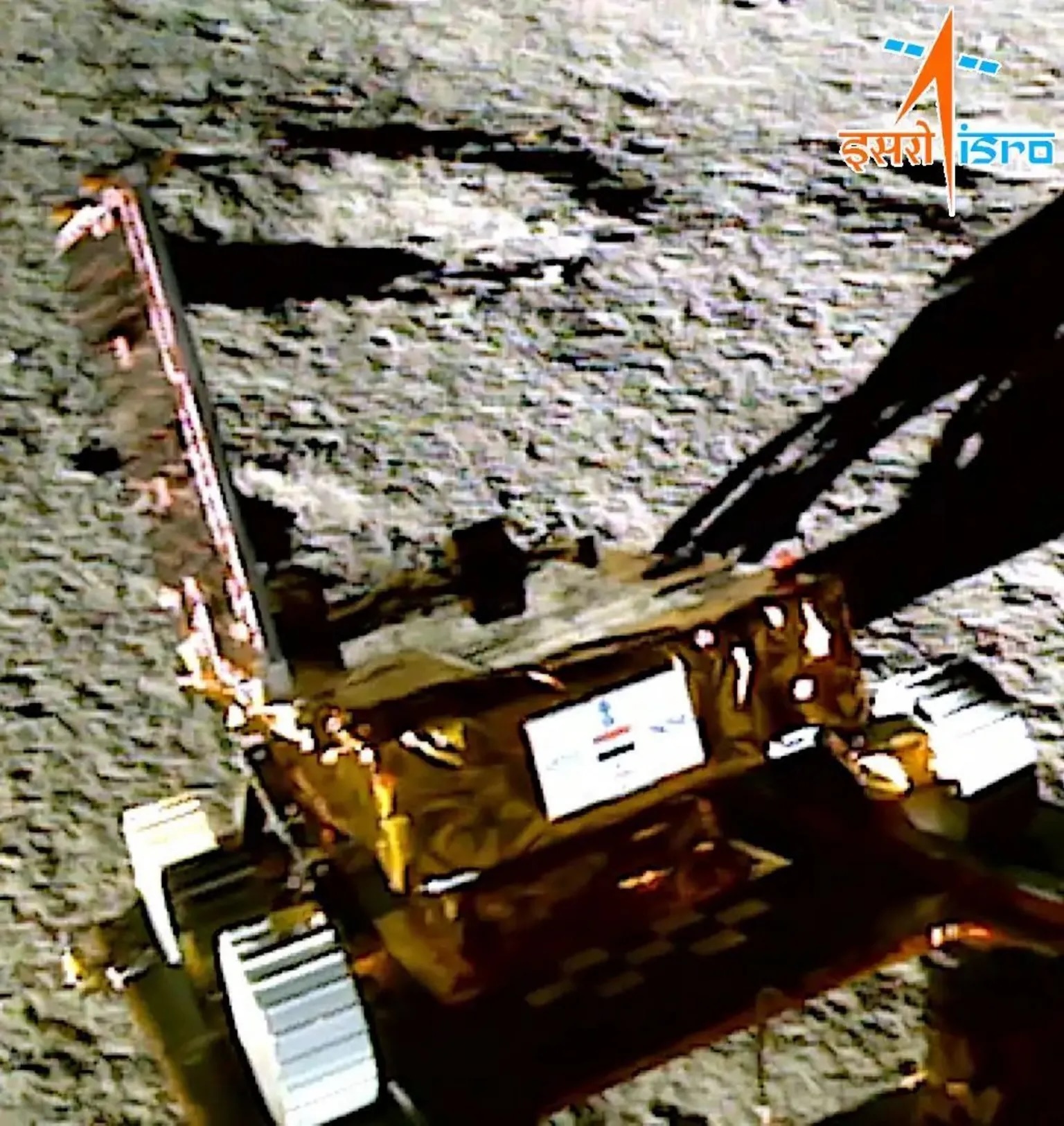

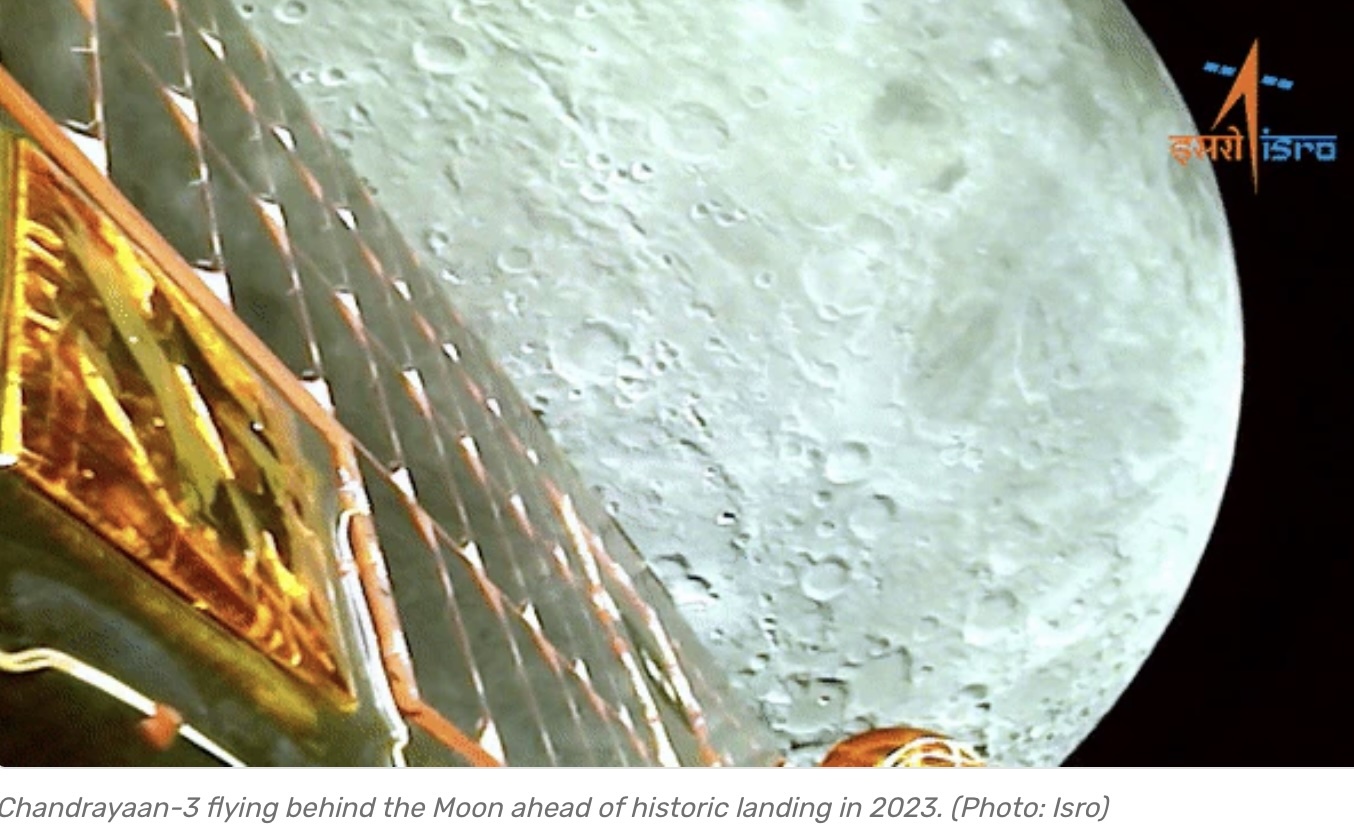

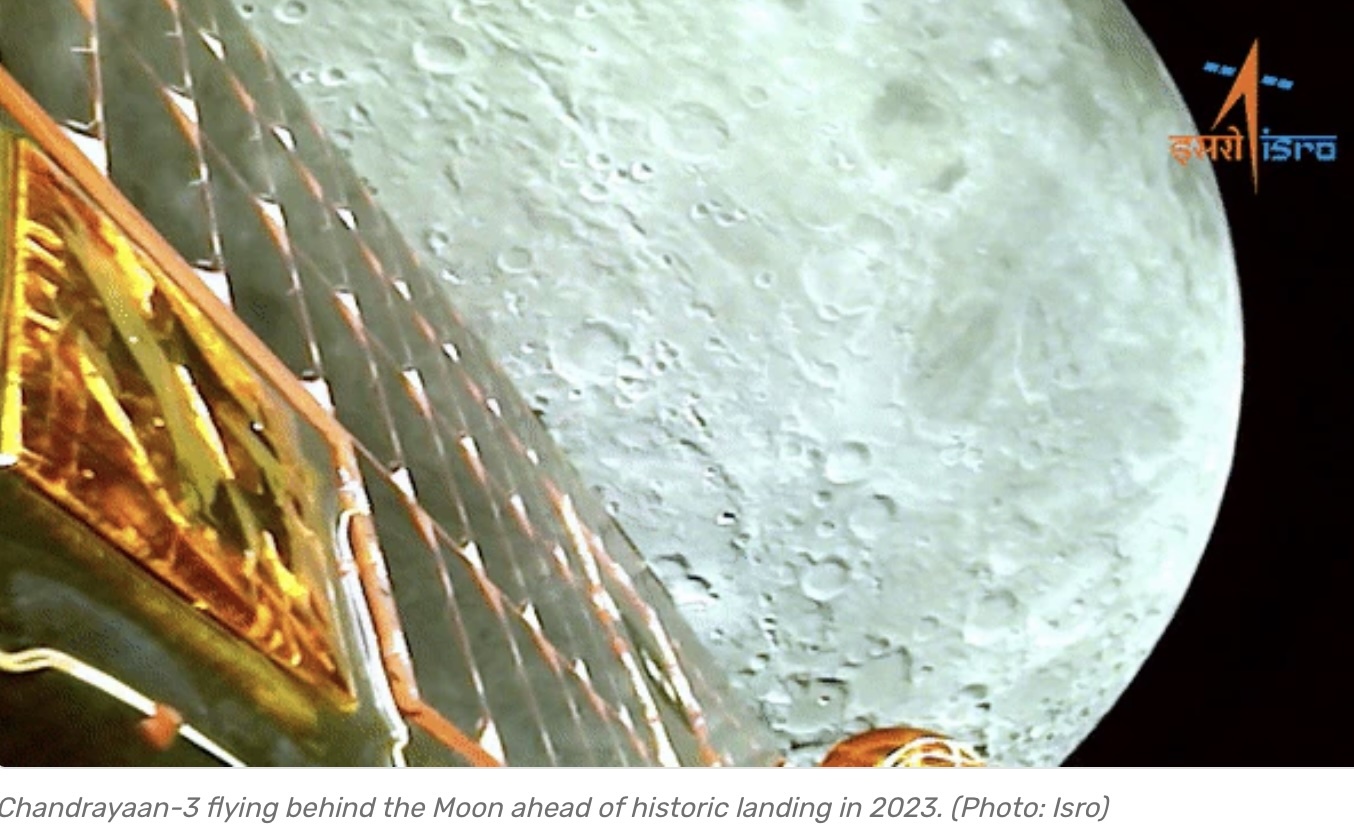

In August 2023, shortly after the Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft notched a flawless touchdown near the lunar south pole, an instrument onboard its lander, called ChaSTE — short for Chandra's Surface Thermophysical Experiment — bored into the moon's soil, reaching a depth of up to 10 centimeters (4 inches) and measured local temperatures over the course of a lunar day.

The recorded data showed temperatures at the spacecraft's landing site that's on a sunward-facing slope — named "Statio Shiv Shakti" — peaked at 179.6 degrees Fahrenheit (82 degrees Celsius) and plummeted to -270.67 degrees F (-168.15 degrees C) during the night. However, just a meter away, where the terrain flattened out and faced toward the pole, the temperature peaks were much lower, reaching just 138.2 degrees F (59 degrees C).

Simulations suggest that slopes greater than 14 degrees in higher latitudes, but facing in the poleward direction, may be cool enough for ice to accumulate at shallow depths. And these conditions are similar to those proposed for future lunar south pole landing missions, including with NASA's Artemis moon missions, the researchers write in their new study:

"Such sites are not only scientifically interesting but also pose less technical challenges for exploration in comparison with regions closer to the poles of the moon."

The study was published on Thursday (March 6) in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 15.11.2025

.

ISRO Tracks Chandrayaan-3 Module As It Re-Enters Lunar Zone

Asteroid-tracking data from September showed that the service module's trajectory will bring it near the Moon twice in early November.

The Chandrayaan-3 service module, last tracked by Space-Track.org on June 27, 2025, has naturally entered the Moon's gravitational influence, according to scientists.

Asteroid-tracking data from September showed that the service module's trajectory will bring it near the Moon twice in early November. The Chandrayaan-3 (CH-3) propulsion module, more than two years after the main mission, naturally drifted close to the Moon.

The Earth, Moon, and Sun's gravitational pull caused the spacecraft to slowly drift without any engine fires. The module is the portion of the spacecraft that helps the mission function in space while carrying Chandrayaan-3 to the Moon without landing.

It is extremely uncommon for a spacecraft to naturally orbit the Moon years after the completion of its main mission. The propulsion module remained in orbit when the lander and rover touched down on the Moon in August 2023. It now naturally moved back near the Moon in 2025.

The module entered the Moon's Sphere of Influence (SOI) on November 4. It's the region where the Moon's gravity is stronger than Earth's. It traveled around 3,740 kilometers above the lunar surface. On November 11, the second flyby took place at a distance of 4,537 kilometers.

The module has become bigger and a bit flatter after the lunar flybys. "The satellite orbit has changed from 1 lakh x 3 lakh km to 4.09 lakh x 7.27 lakh km in terms of size, and its inclination changed from 34 degrees to 22 degrees due to these flyby events," ISRO said in its blog post.

The Indian space agency emphasised that these encounters were not intentional maneuvers; instead, the orbit gradually drifted due to gravitational pull.

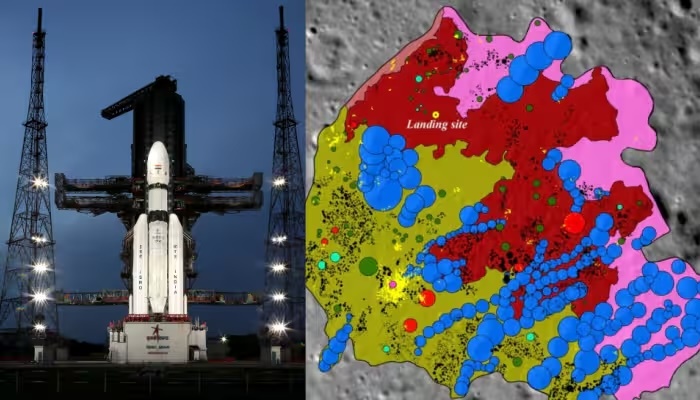

CH-3 was launched on July 14, 2023, from Sriharikota on an LVM3 rocket with the purpose of landing safely on the Moon, operating a rover, and carrying out scientific experiments on the lunar surface.

After its successful Moon landing in August 2023, the Propulsion Module stayed in orbit, then was moved into a higher Earth orbit in October. Over the next two years, it naturally drifted under the pull of Earth and the Moon's gravity.

Quelle: NDTV

+++

Chandrayaan-3 surprises again as its module swings back near the Moon

Chandrayaan-3’s Propulsion Module unexpectedly re-entered the Moon’s gravity zone this month, completing two close flybys that stretched its orbit to new extremes. ISRO says the event offered rare insights into spacecraft behaviour under combined Earth-Moon gravitational forces. The module is expected to exit the lunar zone again today, continuing its long journey around Earth.

New Delhi: This week, the Chandrayaan-3’s Propulsion Module created fresh interest after it slipped back into the Moon’s gravity zone during its long Earth-bound orbit. What looked like a quiet post-mission phase has turned into an unexpected scientific opportunity, giving researchers a close look at how Earth and lunar gravity can reshape a drifting spacecraft’s path.

What started as a simple return-orbit experiment has ended up becoming a cosmic detour that pushed the spacecraft back into the Moon’s gravity field, giving scientists a rare chance to observe how Earth and lunar gravity pull a drifting satellite in different directions. ISRO says this whole event has offered “valuable insights and experience from mission planning, operations, flight dynamics perspectives, and especially enhanced the understanding of disturbance torques effects.”

Chandrayaan-3 module drifts back into Moon’s gravity field

The Propulsion Module has been roaming in a wide Earth-bound orbit since October 2023. It was sent back home after the historic soft landing and rover operations. Since then, the module has been looping around Earth at distances ranging from 1 lakh km to nearly 3 lakh km.

This slow dance changed shape in early November. Gravity from both Earth and the Moon tugged at the module until it entered the Moon’s Sphere of Influence on 4 November 2025. That basically means the Moon’s gravity took control of its path. ISTRAC tracked the odd movement closely, and one scientist joked during an internal briefing that it felt like “watching an old visitor return without warning.”

Two flybys in one week

ISRO confirmed two close passes:

- First flyby on 6 November 2025 at 12:53 IST, roughly 3740 km above the lunar surface.

- Second flyby on 12 November 2025 at 04:48 IST, with a closest approach of 4537 km. This one was visible to the Indian Deep Space Network.

Both events happened without any close approach to other lunar orbiters. ISRO said, “The overall Satellite performance is normal during the flyby and no close approach was experienced with the other lunar orbiters.”

Orbit stretched to new limits

The spacecraft’s orbit changed dramatically after the flybys. What was once a 1 lakh km by 3 lakh km orbit turned into a much larger 4.09 lakh km by 7.27 lakh km path. The inclination also shifted from 34 degrees to 22 degrees. For context, that expansion means the module is travelling far deeper into space on each loop than before.

ISRO explained, “Special care was taken to monitor its trajectory and close proximities from the Beyond Earth Space Objects.”

Why the strange movement matters

For most of us, the Propulsion Module was practically forgotten after 2023. But scientists have been quietly using it as a long-term test platform. This unplanned lunar encounter has given them extra data on:

- How gravity from two big bodies fights for control

- How spacecraft twist under disturbance torques

- How uncertain paths can be predicted in deep-space environments

- How mission planning improves from real long-duration operations

In a way, this module is turning into a traveller that refuses to retire. It keeps slipping into new gravitational zones, reminding everyone how dynamic space really is. ISRO expects it to exit the Moon’s Sphere of Influence again on 14 November 2025, drifting back into a wider Earth-bound orbit.

Quelle: newsn9ne

+++

Chandrayaan-3 Fly-by

Chandrayaan-3 (CH-3) mission is to demonstrate safe and soft landing on Lunar Surface, demonstrate Rover roving on the Moon and conduct in-situ experiments. CH-3 mission consisted the Lander Module, Propulsion Module and a Rover. The satellite was successfully launched on-board LVM3 from SDSC SHAR, Sriharikota on July 14, 2023, at 14:35 Hrs. IST.

After the historic lunar landing of CH3 on August 23, 2023, its Propulsion Module (PM) was operated in its lunar orbit at an altitude of nearly 150 km till October 2023. The PM was then relocated to a high-altitude Earth-bound orbit by executing Trans-Earth Injection (TEI) manoeuvres in October 2023. Since then, CH3-PM was revolving in this orbit under the influence of the Earth's and Moon's gravity fields.

This interplay of gravity fields has led the spacecraft to enter the Moon Sphere of Influence (SOI) on November 04, 2025, where the Moon's gravitation dominates the motion. On November 06, 2025 07:23 UT, the first lunar flyby event took place outside the Indian Deep Space Network (IDSN) visibility at a distance of 3740 km from the Moon's surface. The second flyby event was visible from the IDSN, the closest approach distance was 4537 km from the Moon's surface on November 11, 2025, 23:18 UT. CH3-PM is expected to exit the Moon's SOI on November 14, 2025.

The satellite orbit has changed from 1 lakh x 3 lakh km to 4.09 lakh x 7.27 lakh km in terms of size and its inclination changed from 34 deg to 22 deg due to this flyby events. The flyby event trajectory has been monitored very closely from ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network (ISTRAC), ISRO. A special care was taken to monitor its trajectory and close proximities from the Beyond Earth Space Objects. The overall Satellite performance is normal during the flyby and no close approach was experienced with the other lunar orbiters. This event garnered valuable insights and experience from mission planning, operations, flight dynamics perspectives, and especially enhanced the understanding of disturbance torques effects.

Quelle: ISRO

----

Update: 31.12.2025

.

Chandrayaan-3's RAMBHA-LP Instrument Delivers Critical 'Ground Truth' on the Moon’s Plasma Environment

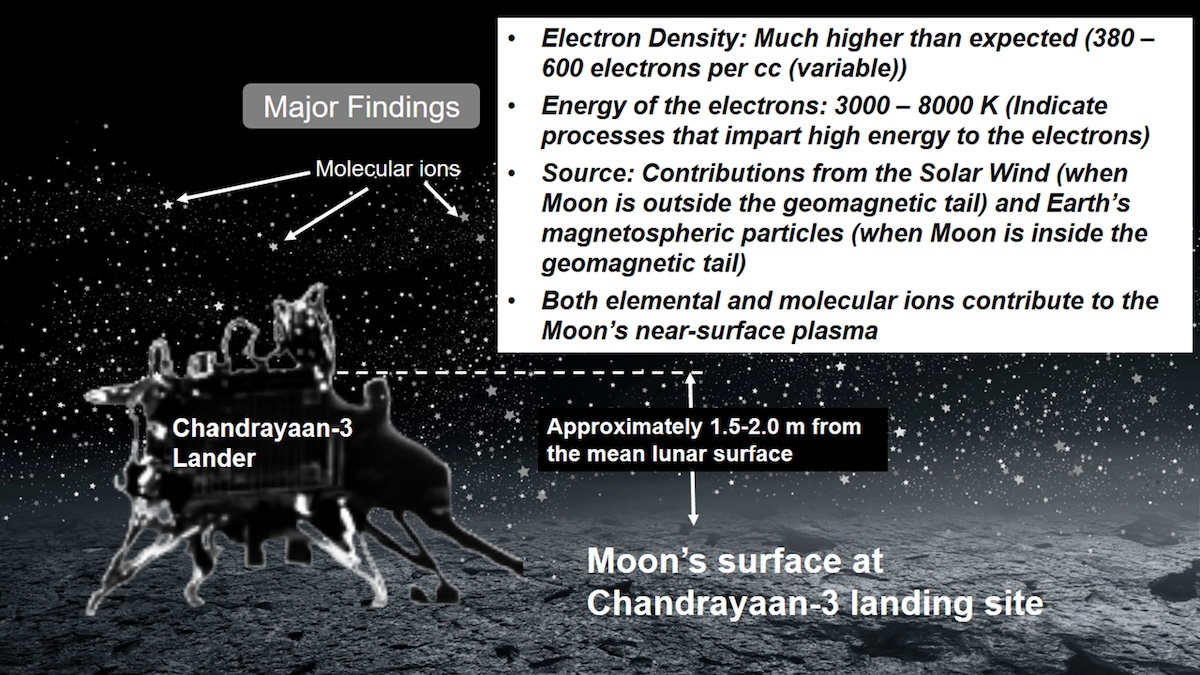

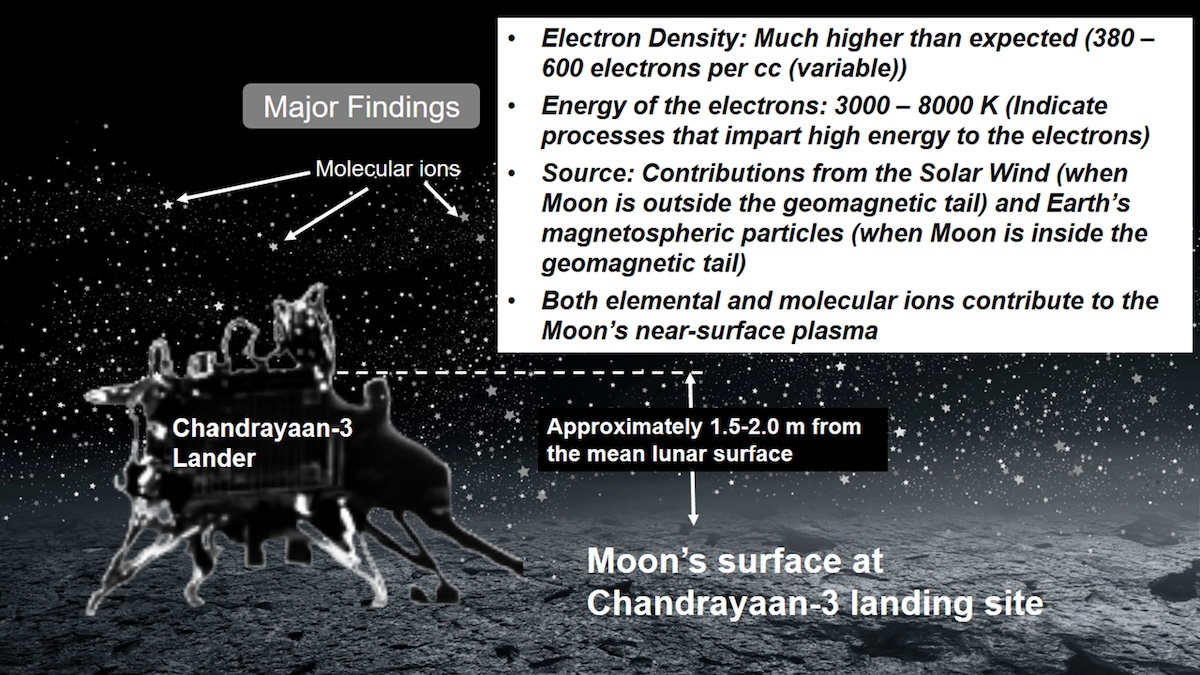

Analysis of the Chandrayaan-3 lander data obtained from data from August 23, 2023 to September 03, 2023 has yielded significant, and first-of-its-kind of results on the plasma environment near the Moon’s surface at the Southern higher latitudes, revealing that the electrical environment near the Moon's surface at the South Polar Region is far more active than previously understood.

In physics, plasma is often called the fourth state of matter, consisting of a mixture of charged particles, including ions and free electrons. Despite being electrically neutral overall, plasma is highly conductive and responds strongly to electromagnetic fields. The Moon's thin plasma environment, or lunar ionosphere, is governed by several major processes. Solar wind, which is a continuous stream of charged particles (primarily electrons, Hydrogen and Helium ions) ejected from the Sun's upper atmosphere, constantly impinges on the Moon's surface. This, along with the photo-electric effect—where high-energy photons from the Sun knock out outer-shell electrons from atoms on the surface and in the sparse atmosphere, causing ionization—is the primary mechanism for creating the plasma. The lunar plasma is further influenced by the deposition of charged particles originating from the Earth's magnetosphere (specifically the magnetotail) when the Moon passes through that region (typically 3-5 days during a period of 28 days), resulting in a constantly changing and dynamic electrical environment near the surface.

In this context, the results, obtained by the Radio Anatomy of the Moon Bound Hypersensitive ionosphere and Atmosphere – Langmuir Probe (RAMBHA-LP) instrument onboard the Vikram lander of Chandrayaan-3, mark the first-ever direct, or "in situ," measurements of the lunar plasma at such low altitudes. The key findings include the fact that the electron density near the landing site of Chandrayaan-3, named as Shiv Shakti point (69.3° S, 32.3° E) was measured to be between 380 and 600 electrons per cubic centimeter. This is significantly higher than estimates derived from observations taken at higher altitudes, which are primarily based on observing the changes in the phase of electromagnetic signals from satellites passing the Moon’s thin atmosphere at grazing angles, a technique known as Radio Occultation.

It is further found that the electrons near the Moon’s surface possess remarkably high energy, with equivalent temperatures (called kinetic temperature) soaring between 3,000 and 8,000 Kelvin.

The study uncovered that the lunar plasma is not static but is constantly modulated by two distinct factors, depending on the Moon's orbital position around the Earth. When the Moon is facing the Sun (lunar daytime) and outside the Earth’s magnetic field, changes in the near-surface plasma are driven by particles from the Solar Wind interacting with the sparse neutral gas (exosphere) on the Moon. In contrary, when the Moon passes through the geomagnetic tail, the plasma changes are caused by charged particles streaming from the tapered region of Earth's long magnetic tail (towards the opposite side of the Sun), known as the geomagnetic tail.

Furthermore, in-house developed Lunar Ionospheric Model (LIM) suggests that apart from the elemental ions, the molecular ions (likely originating from gases like CO2, H2O) also play a crucial role in creating this electrically charged layer close to the lunar surface.

These results from the RAMBHA-LP experiment provide essential ground truth needed for the next phase of lunar exploration.

The RAMBHA-LP experiment was designed and developed by Space Physics Laboratory (SPL), Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC), Thiruvananthapuram.

Quelle: ISRO

+++

In situ ionospheric observations near lunar south pole by the Langmuir Probe on Chandrayaan-3 lander

ABSTRACT

In situ measurements of the near surface lunar plasma environment are made using the RAMBHA-LP (Radio Anatomy of the Moon Bound Hypersensitive ionosphere and Atmosphere-Langmuir Probe) payload onboard India’s Chandrayaan-3 Lander during lunar daytime (2023 August 24 to 2023 September 2). These observations provide estimates of near surface (2 m above the surface) lunar electron density and electron temperature from the south polar region, ‘for the first time’. The estimations reveal the daytime lunar plasma to have mean electron density (N) in the range of 380–600/cc and mean electron temperature (T) in the range of 3000–8000 K. The critical roles of solar wind and the Earth’s magnetospheric particle flux in modulating the lunar dayside ionosphere outside and inside the Earth’s geomagnetic tail, respectively, are unravelled using RAMBHA-LP observations and lunar ionospheric model simulations. The study also highlights the role of molecular species in the genesis of lunar near surface plasma environment.

Quelle: Oxford University