9.10.2019

Artemis Updates

This edition of Artemis Updates brings updates on the Artemis 1 SLS Core Stage, Orion, and Exploration funding. Construction of the Artemis 1 SLS Core Stage has been completed, 12 Orions were ordered by NASA, and the Senate Commerce, Justice, and Science Appropriations Subcommittee gave NASA’s Exploration programs (SLS and Orion) large funding increases.

SLS Core Stage Segments Joined

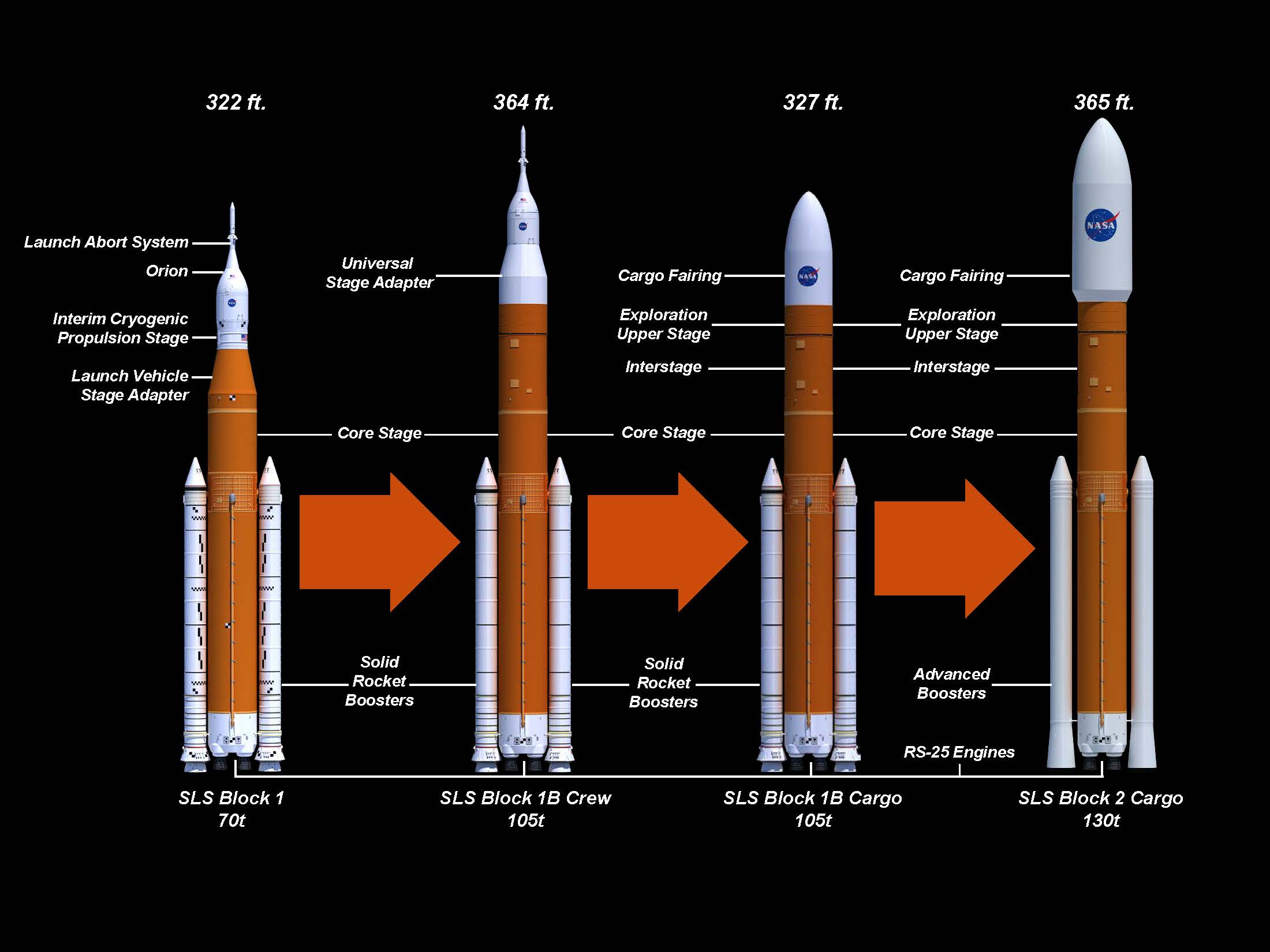

On September 19, NASA, the sole integrator of the SLS rocket, announced that engineers at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF), after a “breakover” when during 48 hours of continuous and careful maneuvering to protect all the critical systems inside the engine section was flipped on its side, had joined the engine section to the 212 foot tall Artemis 1 Core Stage. This completes the structural assembly of the Artemis 1 SLS Core Stage. The SLS Core Stage is the center of the SLS rocket, serving as the attachment for the two solid rocket boosters, avionics, the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion System (ICPS), which is attached to the Orion Crew and Service modules (CSM), and the RS-25 engines.

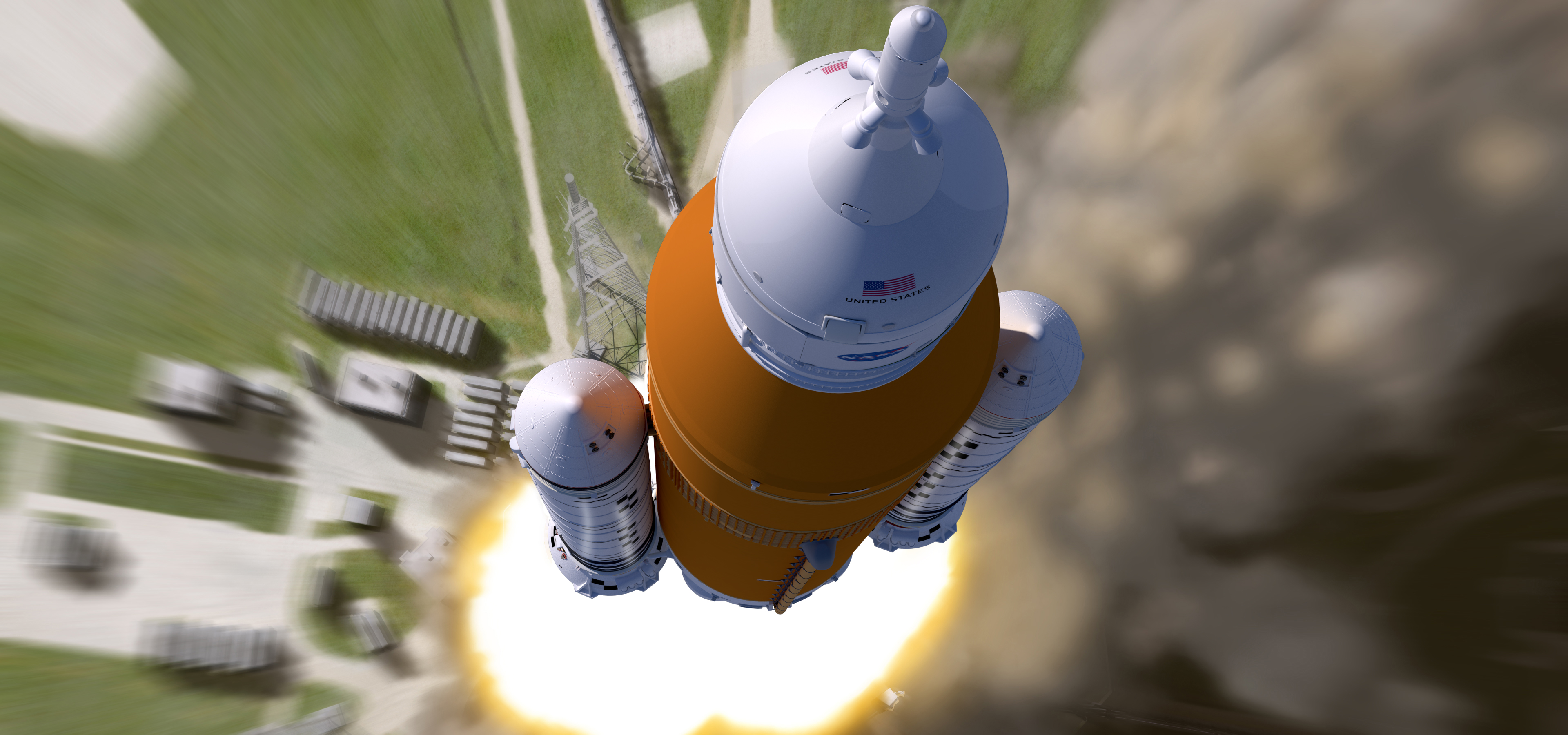

The engine section is one of most complicated parts of the five sections of the SLS Core Stage. Mounted inside of the engine section are the four RS-25 engines that will generate 2 million pounds of thrust. The SLS Core Stage engine section also serves as the lower attachment point for the two solid rocket boosters, both of which produce 6.8 million pounds of thrust. Together, the four RS-25 engines and two solid rocket boosters product 8.8 million pounds of thrust, making the Core Stage engine section the focal point for the loads generated during lift-off of the SLS. The engine section also includes systems needed for mounting, controlling and delivering fuel from the stage’s two liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen (LOX/LH2) tanks to SLS’s four RS-25 engines.

With the joining of the engine section, Boeing and Aerojet Rocketdyne will begin the installation in the engine section of the four RS-25 engines that are sitting, literally, next door to the Artemis 1 Core Stage, and is expected to be completed by the second week in December.

Once the RS-25 engines are installed, the Artemis 1 Core Stage will be rolled-out of MAF, signaling the completion of the construction of the first rocket at MAF since the Apollo era. loaded onto the Pegasus barge, and towed to Stennis Space Center. At Stennis, the Core Stage will be loaded onto the B-2 test stand for the Green Run sometime in the early spring of 2020 that will see the four RS-25 engines ignited and run for the full-duration they will during the Artemis 1 launch. Then the SLS Core Stage will be cleaned-up and shipped to Kennedy Space Center, where it will stacked along with the other parts that make up the SLS rocket in preparation for the Artemis 1 launch sometime in late 2020 or early 2021.

SLS Core Stage Structural Testing Enters Final Quarter

NASA and Boeing also announced on September 19 that the liquid hydrogen test article, which began its structural testing in June, had completed its testing at Marshall Spaceflight Center for the Artemis 1 mission. For the structural test, the liquid hydrogen tank was bolted to a huge 80,000-pound steel ring at the base of the test stand at Marshall Spaceflight Center’s test stand 4693. During the 37 separate test cases that simulated the stresses of launch, dozens of hydraulic cylinders at Test Stand 4693 applied forces to the steel ring that pushed and pulled the giant tank to mimic the same stresses and forces that the SLS Block 1A rocket will endure during liftoff and flight.

Previous to testing the liquid hydrogen tank test article, Marshall Spaceflight Center had subjected test elements of the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion (ICPS) Unit and the Intertank, which completed its testing in June, to structural testing.

The last structural test article, the liquid oxygen (LOX) tank test article, arrived at Marshall Spaceflight Center on July 19th and will, according to NASA, begin its structural testing shortly. The LOX tank structural test article also contains the forward skirt and intertank. Testing will continue on the SLS Core Stage test elements to validate the design is sound for the SLS Block 1B and missions with more extreme stresses. According to Mike Nichols, the test conductor for the liquid hydrogen tank tests, structural testing takes four months. So the beginning of structural testing of the LOX tank test article marks the milestone of Marshall Spaceflight Center entering the final quarter of the largest test campaign since the Space Shuttle. Unlike the Iron Bowl, everyone at Marshall Spaceflight Center is looking forward to reaching the end zone of structural testing of for the Artemis 1 launch and beginning structural testing for SLS Block 1B.

Last Element of Artemis 2 Core Stage Welded

Slipping through the cracks of previous “Artemis Updates” was an August 8 announcement by Boeing that “the last element of Core Stage 2 is being welded ahead of the addition of electrical and propulsion systems. The work is proceeding far more quickly than on the first core stage, thanks to an established production system and lessons learned from building and testing its predecessor. Like Core Stage 1, Core Stage 2 will be incrementally tested throughout the build cycle to ensure functionality and reliability.” Also, Boeing released a picture of the Artemis 2 SLS Core Stage engine section, one of the long-lead items on the SLS rocket, undergoing work. Just as a reminder to our readers, NASA announced on August 15 that the Artemis 3 SLS Core Stage engine section had been ordered.

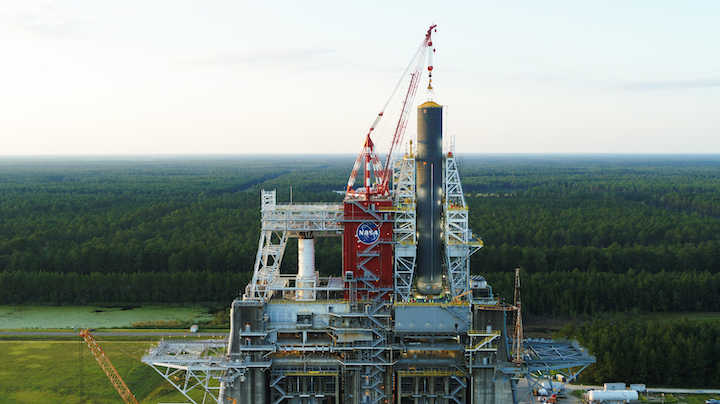

SLS Pathfinder at Stennis’ B-2 Stand

On August 26, NASA announced that the SLS Core Stage Pathfinder was being lifted at the Stennis Space Center’s B-2 test stand. The SLS Core Stage Pathfinder simulates in total weight, weight distribution, and dimensions the 212 foot SLS Core Stage that will be delivered to Stennis Space Center in late December and in early 2020 start its Green Run test at Stennis’ B-2 test stand.

The SLS Core Stage Pathfinder was lifted from its horizontal position on the B-2 Test Stand tarmac with the facility boom crane line attached to the forward end and a ground crane line attached to the aft end. As NASA describes it, “[T]he pathfinder then was “broken over” into a vertical position. Once the ground crane line was disconnected, the core stage pathfinder was lifted into place by the stand boom crane. This “fit test” validated auxiliary lift equipment, procedures, and verified that stand modifications and preparations are in place and prepared for delivery and testing of the SLS core stage flight hardware.”

To prepare for the upcoming Green Run test, Stennis modified or upgraded every major area and system of the B-2 test stand. One major modification to the B-2 test stand was to move the structural framework that will house the SLS Core Stage 20 feet from its previous position from testing the Space Shuttle’s main engines. Additional modifications included a high-pressure industrial water system and high-pressure gas facility that support test operations.