12.07.2022

The first run of a new dark matter experiment turns up nothing — but that still tells us something.

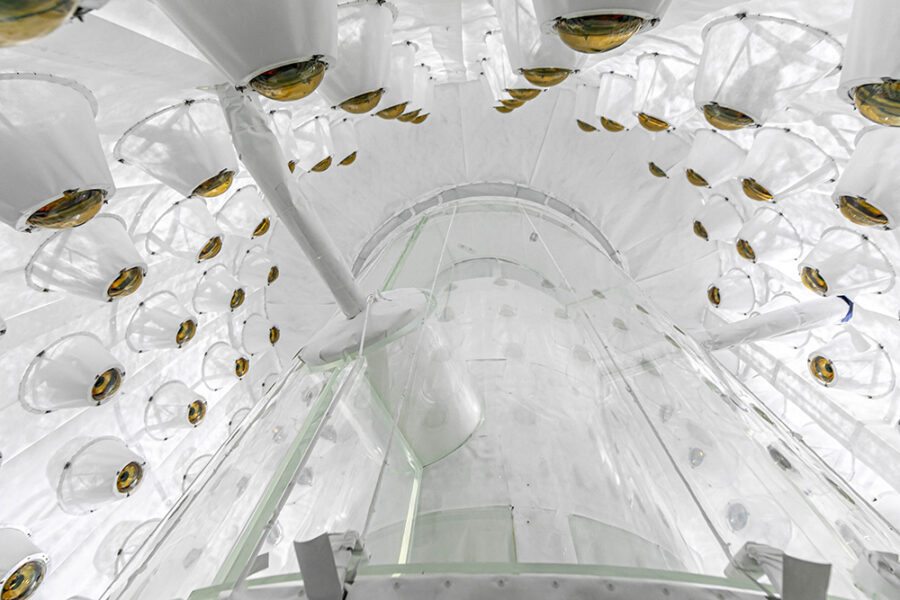

This view looks up into the LZ Outer Detector, which is used to veto radioactivity that can mimic a dark matter signal.

Matthew Kapust / Sanford Underground Research Facility

The first run of the most sensitive dark matter detector in the world has come up empty. Sixty days’ worth of data-taking by the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment failed to show evidence for the mysterious stuff, scientists revealed at a July 7th webinar.

Based on observations of galactic rotation, gravitational lensing, and the cosmic microwave background, astrophysicists conclude that no less than 85% of all gravitating matter in the universe cannot be composed of familiar atoms and molecules. Instead, this invisible (and transparent) dark matter is believed to consist of as-yet undetected elementary particles that do not fit in our current Standard Model of particle physics.

The problem is, they’re extremely difficult to catch, since they hardly interact with “normal” matter at all. One such weakly interacting massive particle (WIMP) would pass unhindered through 10 million light-years of solid lead before hitting an atomic nucleus, explains LZ spokesperson Hugh Lippincott (University of California, Santa Barbara).

Then again, billions of relatively heavy-weight dark matter particles should pass through your body each and every second, so an extremely sensitive detector might be able to succeed in registering rare interaction events every now and then.

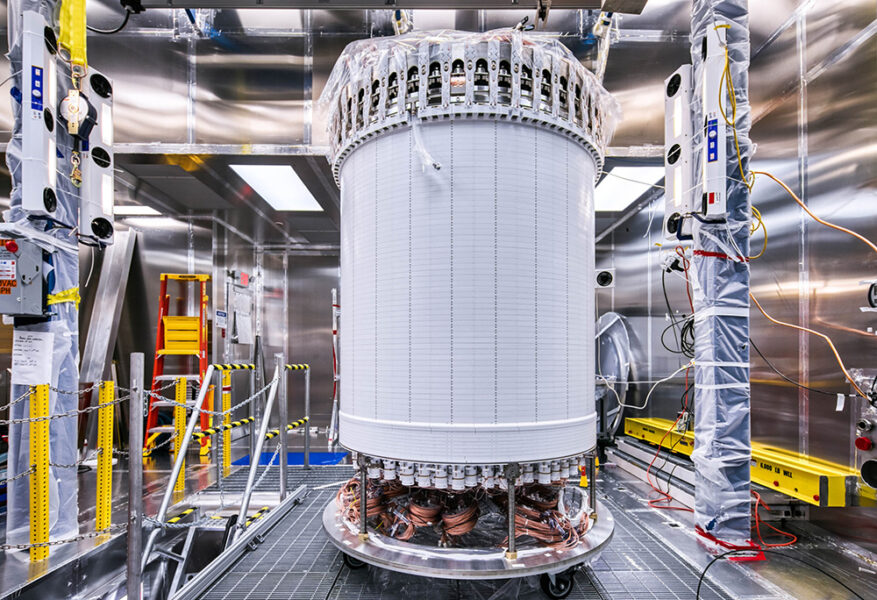

LZ, located in the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) near Lead, South Dakota, uses 7 tons of liquid xenon to look for dark matter. The purified xenon is carefully shielded from all possible sources of background noise, such as cosmic rays and radioactive decay. Almost 500 photomultiplier tubes are on the lookout for the tiny flashes of light that would result, should a WIMP crash into a xenon nucleus.

In a paper posted on the LZ website, the collaboration of some 250 researchers from 35 institutes in four countries (the USA, the United Kingdom, Portugal, and Korea) present their analysis of the first 60-day science run, which commenced late last year. The bottom line: Everything works as expected, or even slightly better, but the instrument didn’t detect any WIMPs.

Matthew Kapust / Sanford Underground Research Facility

Not yet, that is. “We plan to collect about 20 times more data in the coming years,” Lippincott said in a press statement, “so we’re only getting started. There’s a lot of science to do and it’s very exciting!”

“It’s a bit of a pity of course,” says Auke-Pieter Colijn (Nikhef Dutch National Institute for Subatomic Physics), who is the technical coordinator of a competing dark matter detector in Italy, “but it’s not unexpected. You start with a brief run to show that everything works fine. You’d have to be extremely lucky to secure a detection right away.”

The Italian detector, known as XENONnT, has also completed its first 100-day run. Data analysis is in full swing; Colijn expects the results to be presented within a few months at most.

If the current generation of xenon-based detectors won’t find any evidence for WIMPs, a much larger and more sensitive instrument might. Last month, three international collaborations (XENON, LZ, and DARWIN) announced they would join forces in designing (and hopefully building) “one more xenon experiment to rule them all,” as LZ physics coordinator Eric Broberg (SURF) puts it. The dark matter hunters aren’t giving up just yet.

Quelle: Sky&Telescope